Guangxi Massacre: The Deadliest Episode of China’s Cultural Revolution

Fueled by Maoist fanaticism, Guangxi witnessed a horrifying collapse of civilisation, where political ideology justified mass killings, torture, and acts of public cannibalism. Read the full article to uncover the harrowing truth...

Total Views |

Cannibalism is feasibly the ugliest expression of mankind, where a human eats a fellow human, not for survival but as a puppet of an ideological hatred, and this manifestation of ‘ideological hatred’ marks a collapse of civilisation. And this collapse was witnessed by the whole world when Mao’s fanaticism turned neighbour against neighbour, and the red revolution of hatred consumed the whole nation.

Dated between the years 1967 and 1968, the streets of Guangxi witnessed beheading, beating, live burials, stoning, drowning, boiling, group slaughters, disembowelling, digging out of hearts, livers, and genitals, slicing off of flesh, and blowing up with dynamite, all in the name of class struggle.

Guangxi Massacre — China’s Cultural Revolution

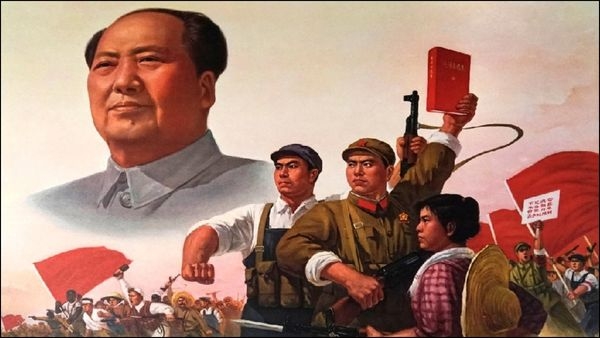

In 1966, Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution to purge “counter-revolutionaries” and “class enemies” within the Communist Party and Chinese society. Chaos spread nationwide as the ‘Red Guards’, radical youth groups, attacked officials, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens accused of being “reactionary”. Crafting the draft of the Guangxi Massacre and leading to the barbaric episodes of mass violence that occurred during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), primarily between 1967 and 1968, in Guangxi Province, southern China.

The Cultural Revolution of Mao Zedong lasted until his death in 1976.

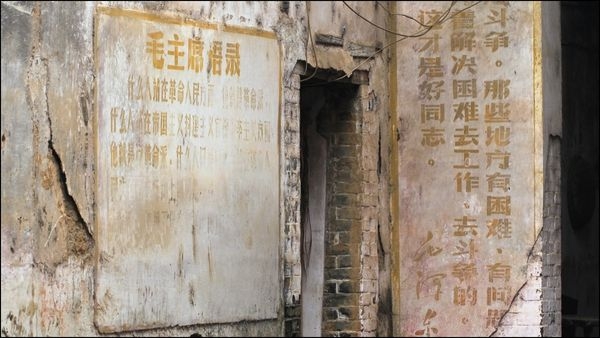

Beginning in 1966, with the help of the Cultural Revolution Group, Mao launched the revolution and lamented to the masses that bourgeois elements had infiltrated the government and society with the aim of restoring capitalism. Mao called on young people to bombard the headquarters and actively proclaimed that “to rebel is justified”. Mass upheaval began in Beijing with Red August in 1966. Many young people, mainly students, responded by forming cadres of Red Guards throughout the country. Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung became revered within his cult of personality. In 1967, emboldened radicals began seizing power from local governments and party branches, establishing new revolutionary committees in their place while smashing public security, procuratorate and judicial systems. These committees often split into rival factions, precipitating armed clashes among the radicals. The whole Cultural Revolution was characterised by violence and chaos across Chinese society.

Murder of Masses

Mao’s cultural revolution brought political fanaticism to the state, which devolved into mass murders.

In areas such as Wuxuan County, Wuming, and Nanning, hundreds of incidents of human cannibalism occurred even though there was no famine or food shortage. Victims labelled as “class enemies” or “counter-revolutionaries” were executed, and their hearts, livers, and flesh were cut out and consumed in public as “revolutionary rituals” which were meant to demonstrate loyalty to Mao Zedong and the Communist Party. According to initial official records, at least 137 people were eaten, with thousands participating; later investigations raised the number to over 300, and independent researchers have identified at least 421 named victims, with reports spanning dozens of counties. The evidence suggests that the local Communist Party offices and Revolutionary Committees not only condoned but even organised such acts.

According to Yan Lebin, a member of the Ministry of Public Security who participated in the official investigations of the Guangxi Massacre after the Cultural Revolution, there were three stages of the massacre.

1. The first stage of the massacre mostly took place in the rural areas of Guangxi between the fall of 1967 and the spring of 1968. Most of the victims at this stage were members of the Five Black Categories and their families, including many who supported the “4.22” faction (the rebel faction).

2. The second stage of the massacre took place in the spring and summer of 1968 when most counties in Guangxi had established their revolutionary committees. Most of the massive killings at this stage were organised by the committees and were conducted towards members of the “4.22” faction and their supporters.

3. The third stage of the massacre took place in the summer of 1968, during which massive killings had spread from rural regions to cities in Guangxi. In particular, in July and August 1968, a large number of troops from the Guangzhou Military Region, together with members of the “United Headquarters” (the conservative faction), attacked major cities such as Nanning and Guilin, which were under control of the “4.22” faction. Tens of thousands of people were killed or executed.

In addition to hundreds of cases of cannibalism, victims were slaughtered using barbaric methods, including beheading, beating, live burial, stoning, drowning, boiling, disembowelling, digging out hearts, livers, and genitals, slicing off flesh, blowing up with dynamite, and more. In one instance, a person was bound with dynamite and blown into pieces in a ritual called “heavenly maiden scattering flowers”, orchestrated by Cen Guorong, a former Guangxi Trade Union director and representative at multiple CCP National Congresses. In another case in 1968, Wu Shufang, a geography instructor at Wuxuan Middle School, was beaten to death by students; her body was carried to the Qian River, where another teacher was forced at gunpoint to remove her heart and liver, which were then barbecued and consumed by pupils back at the school.

Documentation & Investigation of Massacre by the Later CCP

In April 1981, the Chinese Communist Party initiated a formal investigation into these atrocities. An investigative group of over 20 people was formed under the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the General Office and Organisation Department of the CCP, the Ministry of Public Security, the Supreme People’s Court, and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate to document, analyse, and account for the massacres.

In June 1981, the investigation concluded that the death toll was over 100,000, while some officials and civilians claimed privately that the death toll was 150,000, 200,000 or even 500,000. In addition, Qiao Xiaoguang reported to the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection that the death toll was 70,400.

In March 1983, another investigation group of 40 people was formed by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

In January 1984, the investigation concluded that 89,700 deaths could be identified by names and addresses, over 20,000 people were missing, and over 30,000 deaths could not be identified by names or addresses. In particular, due to the violent struggles between the two opposing factions, 3,700 people died during direct fighting, 7,000 were persecuted to death, while 79,000 were beaten or shot to death in a planned and systematic manner. In Nanning, the capital of Guangxi, eight out of fourteen counties saw a death toll of over 1,000, with Binyang County alone losing 3,777 people.

From the Archives of the Guangxi Massacre

In 2006, Su Yang of the University of California, Irvine, identified the Guangxi Massacre as the most severe episode of mass violence during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Examining 65 accessible official county documents from Guangxi, he found that 43 counties reported local massacres, with 15 counties recording death tolls exceeding 1,000 and an average of 526 deaths among all counties that reported massacres. Scholar Song Yongyi further highlighted discrepancies between published and classified official data: for instance, Lingshan County’s published annals reported only eight deaths, while its classified documents recorded 3,220 victims; similarly, Binyang County’s public record noted 37 deaths compared to 3,951 in its classified files. In his work Massacres during the Cultural Revolution, Song argued that most massacres of the period were executed by state apparatuses, representing direct violence by the regime against its citizens.

Article by

Kewali Kabir Jain

Journalism Student, Makhanlal Chaturvedi National University of Journalism and Communication