Ancient Science in the Modern Sky: The Story of Chandrayaan-1

From Vedic imagination to lunar exploration, Chandrayaan-1 reflected Bharat’s evolving journey of curiosity, courage, and cosmic understanding.

Total Views |

When the Indian tricolour virtually touched the lunar surface on 14 November 2008, it was a civilisational statement. Chandrayaan-1, India’s first mission to the Moon, marked the reawakening of Bharat’s age-old cosmic curiosity, merging ancient wisdom with modern technological prowess.

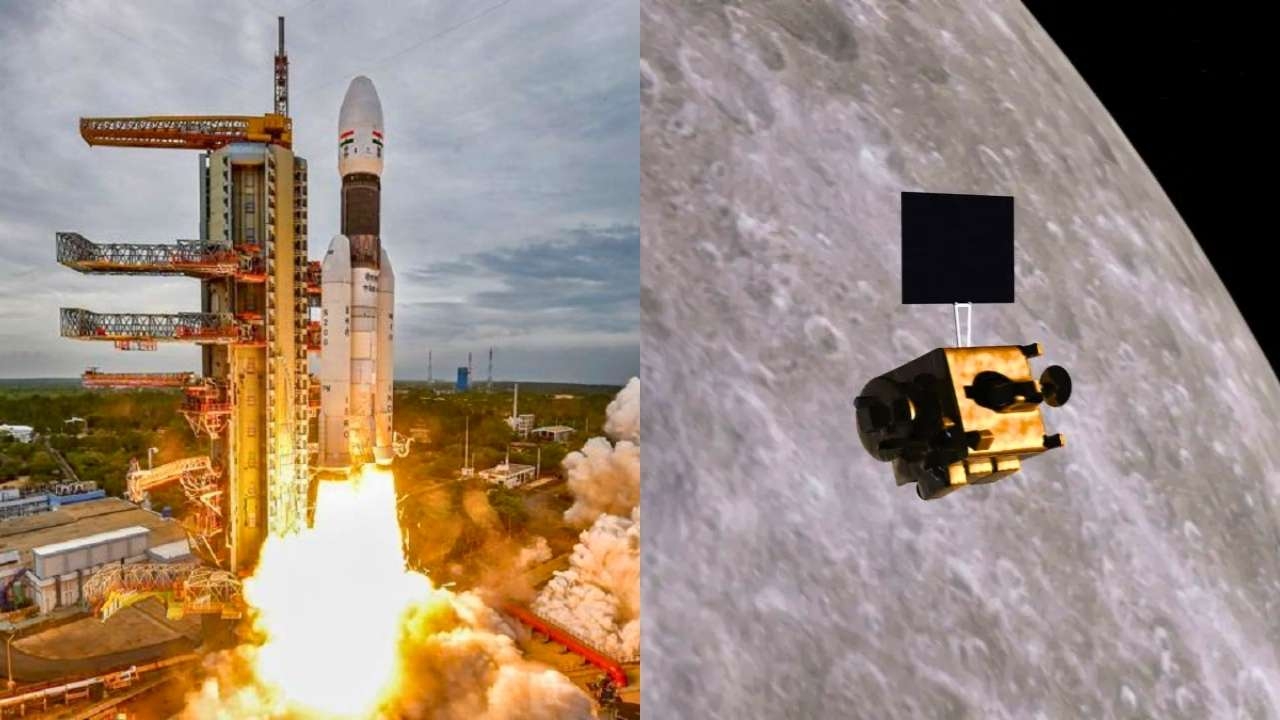

Chandrayaan-1 (from Sanskrit: Chandra – “Moon” and Yāna – “Craft” or “Vehicle”) was the first lunar mission under India’s Chandrayaan programme. Launched by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) on 22 October 2008 at 00:52 UTC, the mission represented a monumental milestone in India’s space journey.

The spacecraft, comprising an orbiter and an impactor, was launched aboard the PSLV-XL (C-11) rocket from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre (SDSC), Sriharikota, Andhra Pradesh. On 8 November 2008, Chandrayaan-1 was successfully inserted into lunar orbit, symbolising India’s arrival as a capable and confident spacefaring nation.

On 14 November 2008, the Moon Impact Probe separated from the Chandrayaan orbiter at 14:36 UTC and struck the lunar south pole in a controlled manner. The probe impacted near the Shackleton crater at 15:01 UTC. The location of the impact was named Jawahar Point. With this mission, ISRO became the fifth national space agency to reach the lunar surface. The other nations whose space agencies had achieved similar feats were the former Soviet Union in 1959, the United States in 1962, Japan in 1993, and the European Space Agency member states in 2006.

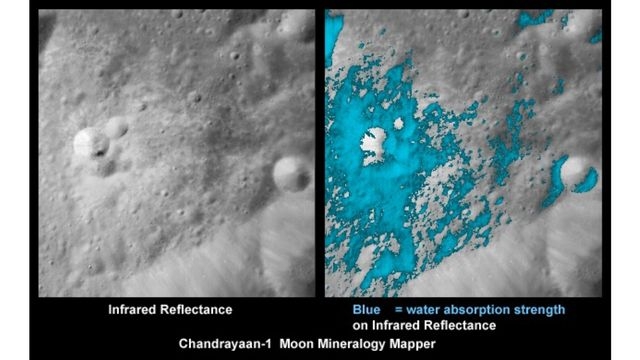

The estimated cost of the project was ₹386 crore (US$88.73 million). It was designed to survey the lunar surface for over two years, producing a complete map of the chemical composition at the surface and its three-dimensional topography. The polar regions were of special interest as there was a high possibility of finding water ice. One of its many achievements was the discovery of the widespread presence of water molecules in the lunar soil.

After almost a year, the orbiter began experiencing several technical issues, including failure of the star tracker and inadequate thermal shielding. Chandrayaan-1 stopped communicating at about 20:00 UTC on 28 August 2009, shortly after which ISRO officially declared the mission over. Although Chandrayaan-1 operated for 312 days instead of the intended two years, the mission achieved most of its scientific objectives, including detecting the presence of lunar water.

On 2 July 2016, NASA used ground-based radar systems to relocate Chandrayaan-1 in its lunar orbit, almost seven years after it had shut down. Repeated observations over the following three months allowed a precise determination of its orbit, which varies between 150 and 270 km (93 and 168 miles) in altitude every two years.

Former Prime Minister of India, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, announced the Chandrayaan-1 project, which proved to be a major boost to India’s space programme. The idea of an Indian scientific mission to the Moon was first raised in 1999 during a meeting of the Indian Academy of Sciences. The Astronautical Society of India (ASI) began planning the implementation of such an idea in 2000. Soon after, ISRO set up the National Lunar Mission Task Force, which concluded that the organisation had the technical expertise to carry out an Indian mission to the Moon.

In April 2003, over 100 Indian scientists from diverse fields, including planetary science, space sciences, Earth sciences, physics, chemistry, astronomy, astrophysics, engineering, and communication sciences, discussed and approved the Task Force recommendation to launch an Indian probe to the Moon. Six months later, in November, the Vajpayee government formally approved the mission.

Objectives and Discovery

The primary objectives of the Chandrayaan-1 mission were to create a high-resolution three-dimensional map of the entire lunar surface and to conduct a comprehensive chemical and mineralogical mapping to study the distribution of key elements such as iron, magnesium, and titanium. A critical technological objective was to successfully test the Moon Impact Probe (MIP), which was designed to make a controlled hard landing near the Moon’s South Pole to prepare for future soft-landing missions.

While achieving over 95% of its goals despite an early end to its operational life, the mission’s most significant discovery was the conclusive detection of water molecules (H₂O) and hydroxyl (OH) on the lunar surface. This finding, primarily through the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) instrument, was a breakthrough that fundamentally altered the global scientific understanding of the Moon, revealing that it is not entirely dry and may hold resources vital for future human exploration.

Article by

Kewali Kabir Jain

Journalism Student, Makhanlal Chaturvedi National University of Journalism and Communication