Vande Mataram - The War Cry of Resistance

Banned by the British but sung by millions, Vande Mataram turned fear into courage and faith into a weapon of resistance

Total Views |

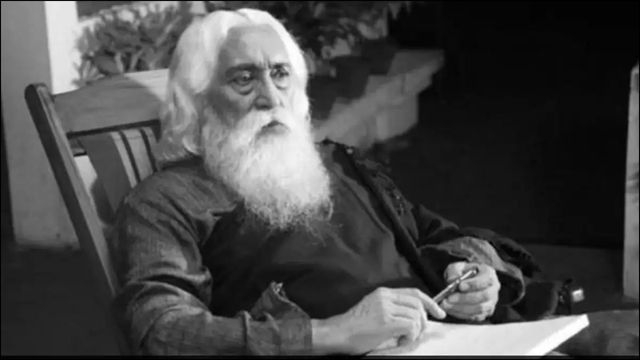

Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore, in his essay The Religion of the Artist (1924), wrote, “I was born and brought up in an environment of three movements, all of which were radically awakening… there was a second movement… Bankimchandra Chatterjee, who was the first pioneer in the literary awakening which happened in Bengal…”

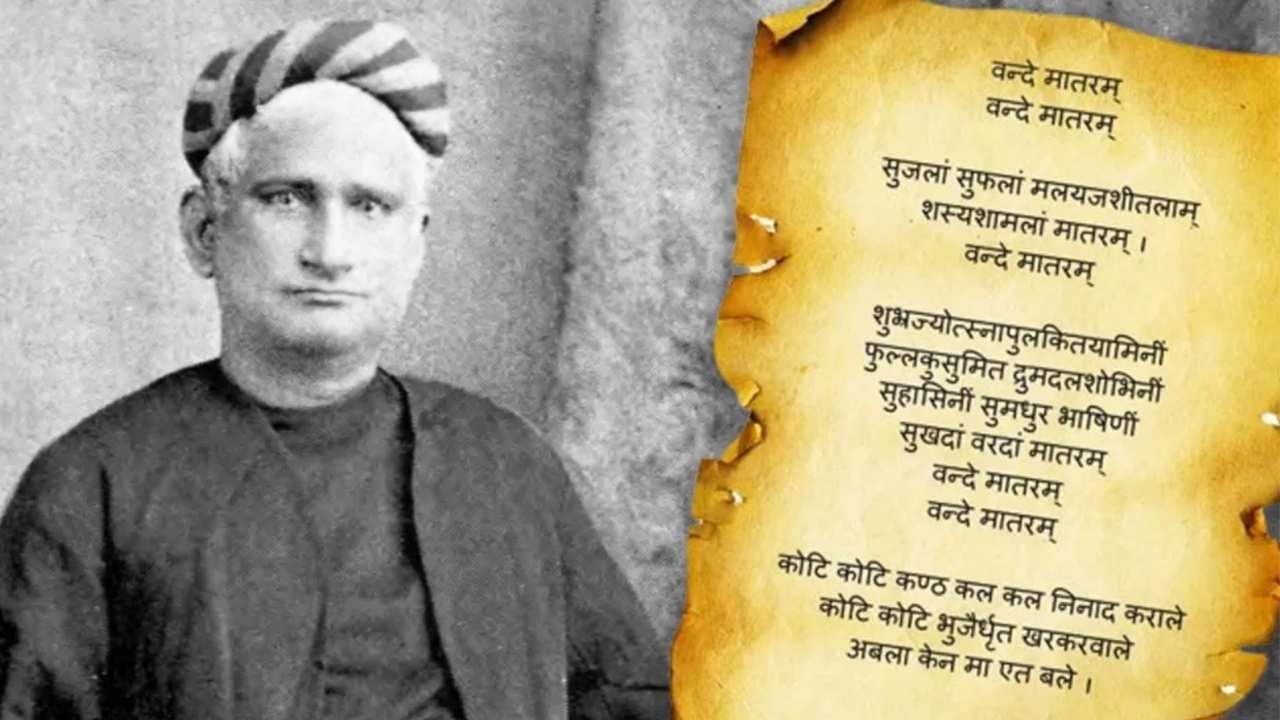

The movement mentioned by Gurudev is the penned prayer of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee to Bharat Mata.

In 1876, a revolution stirred the hearts of Bengal when the echoes of glory to Bharat Mata were first voiced together, shaping the consciousness of an entire civilisation. It was the year Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, a devout patriot, philosopher, and literary giant, penned Vande Mataram – a song that became the roar of India’s independence.

The poem personifies the land as a mother goddess, a vision deeply rooted in India’s civilisational consciousness. Initially inspired by Banga Mata (Mother Bengal), Bankim’s words transcended regional boundaries to become the collective voice of Bharat Mata herself. As the Indian nationalist and philosopher Sri Aurobindo later wrote, “Vande Mataram is the National Anthem of Bengal and of the awakening nation.”

The spiritual energy of Vande Mataram soon transformed into a political force. When Rabindranath Tagore first sang it at the Indian National Congress session in 1896, a new era of patriotic consciousness began. By 1905, during the Swadeshi movement, the song had become the marching rhythm of revolutionaries who saw the Motherland as sacred and inviolable.

The British rulers feared it – and rightly so. They banned Vande Mataram and the novel Anandamath (in which the song first appeared), threatening imprisonment for anyone who sang it publicly. Yet, instead of silencing India, this only deepened the song’s power. To sing Vande Mataram became an act of rebellion against the British.

The first two verses of the song make abstract reference to the “mother” and “motherland”, praising Bharat Mata. The later verses mention the goddesses Durga, Lakshmi, and Saraswati, symbolising strength, prosperity, and knowledge. They represent the Shakti that resides in the very soil of Bharat.

‘Vande Mataram’ - The War Cry of the Sanyasis

Bhupendranath Dutta, younger brother of Swami Vivekananda, wrote that, according to the Maharashtrian priest at the Ramana Kali Temple of Dhaka, the popular usage of Vande Mataram began when the Sanyasi rebel fighters used it as their battle cry.

The incident dates back to the time when Robert Clive gained the Diwani (right) of Bengal in August 1765 for the East India Company, granting it authority to collect taxes and execute civil justice after defeating Mir Qasim at Buxar in 1764. He used this Dwaita Shasan (Double Governance) system to serve both the Company’s interests and those of the Nawab of Murshidabad. Clive appointed Reza Khan as Naib Diwan of Subah Bengal. Reza Khan became the virtual ruler of Bengal, wielding uncontrolled power from 1765 to 1770.

After Clive, Warren Hastings sought to restrain Reza Khan by appointing Company officers as district supervisors. Despite such checks, Reza Khan drastically increased taxes by ten per cent, neglecting the economic hardships caused by previous years of drought and crippling the local economy.

Bands of warrior Sanyasis, essentially Dashnami Naga ascetics, traditionally roamed Northern Bharat. Some became active in Bengal during the early 1770s and were even involved in the complex succession struggle of Cooch Behar, then an independent state. In this process, the Sanyasis eventually found themselves opposed to the British. These Dashnami Sanyasis were traditionally entitled to collect debts and receive their share of revenue from the Zamindars. As Gurus, they were entitled to Dakshina.

Due to the enhanced taxation by Reza Khan, Zamindars appealed to the Company to strengthen their weakening exchequer. Instead of curtailing their own revenue demands, the Company cancelled or readjusted the Zamindars’ debts to the Sanyasis. The Company then barred the Sanyasis from collecting alms or Dakshina from landlords and farmers, and from visiting certain pilgrimage sites, disrupting their traditional way of life.

This led the ascetics to resort to armed resistance. David Neal Lorenzen, a renowned British-American historian and scholar of religious studies, concluded, “This led to animosity between the Sanyasis and the British.” The Bengali Hindus were oppressed first by Muslim invaders and later by the British, leaving them neither emotionally nor financially capable of fighting back. The Sadhus gave direction and encouragement to the oppressed, urging them to resist their oppressors. The Sanyasis of the Naga, Giri, and Puri sects took the lead in the rebellion.

‘Vande Mataram’ in Bharat’s Independence Movement

The British colonial government, alarmed by the patriotic fervour inspired by Vande Mataram, banned the book Anandamath and made the public recitation of the song a punishable offence. Yet, the song continued to echo across the nation, sung defiantly by workers, students, and freedom fighters in open defiance of the ban.

Rabindranath Tagore first sang Vande Mataram at the 1896 Calcutta Congress Session, followed by Dakhina Charan Sen in 1901 and Sarala Devi Chaudhurani at the Benares Session in 1905. Lala Lajpat Rai launched a journal titled Vande Mataram from Lahore, while filmmaker Hiralal Sen ended India’s first political film (1905) with its chant. The immortal cry “Vande Mataram!” were also the last words of revolutionary Matangini Hazra as she fell to British bullets.

In 1907, freedom fighter Bhikaiji Cama unfurled the first version of India’s national flag in Stuttgart, Germany, with Vande Mataram emblazoned across it. The song continued to inspire revolutionaries – Pandit Ram Prasad Bismil even included his own poetic tribute to Vande Mataram in his banned book Kranti Geetanjali (1929).

Mahatma Gandhi himself defended the song’s sanctity. In a 1946 speech in Guwahati, he insisted that while “Jai Hind” was a worthy greeting, it should never replace Vande Mataram. Gandhi reminded the nation that Vande Mataram had been sung since the inception of the Congress and symbolised the sacrifices that had built the freedom movement.

Article by

Kewali Kabir Jain

Journalism Student, Makhanlal Chaturvedi National University of Journalism and Communication