IFFK 2025 Controversy: Exposing Misinformation, Ideological Propaganda, and Media Bias

Ideological framing by sections of the media transformed an administrative decision into a political spectacle, sidelining legal context in favour of emotive narratives on suppression.

Total Views |

The controversy surrounding the denial of screening permission for 19 films at the 30th International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) has been rapidly transformed from a procedural regulatory issue into a politically charged narrative about artistic suppression.

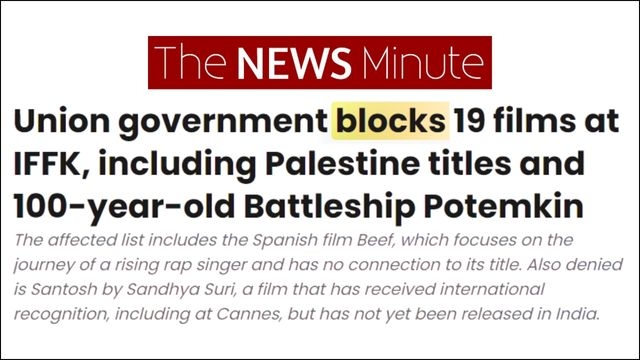

Several media outlets, most prominently The News Minute, have framed the decision of the Union Ministry of Information and Broadcasting as a sweeping “ban” on global cinema, particularly films dealing with Palestine and even a century-old classic such as Battleship Potemkin.

This portrayal, however, collapses under scrutiny. A close, fact-based examination reveals selective reporting, ideological framing, and a deliberate omission of legal and procedural context.

What transpired at IFFK was not an arbitrary act of censorship but the enforcement of an existing legal framework governing public film exhibitions in India. Films screened at festivals do not require full censor certification, but they must obtain a statutory exemption from the Union Ministry.

This requirement has existed for years and applies uniformly to all festivals. In the present case, the Ministry declined to grant exemptions to 19 films at the time of screening, citing procedural and regulatory reasons. Characterising this as a “ban” is inaccurate and misleading.

The festival organisers submitted 187 films for exemption. Of these, 168 were cleared. The remaining 19 did not receive approval before scheduled screenings. Reports indicate that several applications were submitted late, compressing the review timeline and triggering regulatory caution.

This crucial detail is consistently underplayed or ignored in ideologically tilted reportage, which instead foregrounds emotional language around “suppression” and “cultural assault.”

The list of affected films itself dismantles the simplistic narrative being pushed. It includes a wide spectrum of cinema: Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, Spanish film Beef, African works such as Timbuktu and Bamako, Argentine political documentaries, Egyptian drama, and Indian films like Santosh.

The diversity of subjects and origins makes it evident that the Ministry’s action was not targeted at a single ideology or geopolitical narrative.

Contrary to claims of a blanket ban, the Centre subsequently granted exemptions to several films after further review, including Battleship Potemkin, Beef, Bamako, and Heart of the Wolf.

This development alone exposes the falsity of claims that the government intended to permanently suppress these works. The story, however, was rarely updated with equal prominence by outlets that had aggressively framed the initial denial as authoritarian overreach.

A significant strand of commentary has attempted to portray the issue as an attack on Palestinian voices or an anti-Islamic cultural stance. This interpretation is unsupported by facts. Films dealing with Palestine were part of the affected list, but they were neither singled out nor permanently prohibited.

India maintains diplomatic sensitivities across multiple global conflict zones, and films addressing ongoing geopolitical flashpoints are routinely subject to additional scrutiny. This is standard international practice, not ideological persecution.

The controversy also became a rallying point for Left-aligned commentators and Communist party figures, who framed the exemptions issue as proof of shrinking democratic space. Such assertions ignore both the legal obligations of the Ministry and the fact that similar exemptions have been denied in previous years, albeit in smaller numbers. The scale this year reflects administrative timing and the nature of submissions, not a sudden ideological crackdown.

Media conduct in this episode warrants serious examination. The News Minute repeatedly used language such as “blocks” and “bans” without explaining the statutory exemption process or acknowledging subsequent clearances. Government rules, procedural timelines, and legal obligations were either buried or omitted, while protest statements were amplified without scrutiny. This is not balanced journalism; it is narrative construction.

Responsible reporting demands that regulatory decisions be examined in full context. Instead, selective facts were presented to reinforce a predetermined ideological conclusion. Readers were led to believe that artistic freedom itself was under attack, when the reality was a dispute over compliance, review timelines, and regulatory authority.

Criticism from filmmakers and cultural figures must also be contextualised. Statements describing the decision as “ignorant” or “anti-cinema” reflect personal and artistic frustration, not legal analysis.

The availability of a film on public platforms or its status as a classic does not exempt it from statutory requirements for public exhibition in India. Law does not operate on sentiment or legacy.

The Union government’s approach, viewed dispassionately, reflects adherence to due process rather than hostility to cinema. The subsequent granting of exemptions demonstrates flexibility within the framework of law. It also underscores that the intent was regulatory caution, not ideological censorship.

This episode ultimately reveals less about the state of artistic freedom and more about the state of public discourse. A procedural issue was deliberately inflated into a moral crisis, aided by selective reporting and ideological framing. Islamist and Communist narratives found convenient ground in emotional storytelling, while legal facts were sidelined.

The IFFK controversy should serve as a reminder that democratic debate requires intellectual honesty. Regulatory enforcement is not censorship, procedural delay is not suppression, and disagreement with government decisions does not justify distortion of facts.

Media outlets carry the responsibility to inform, not inflame. When they fail to do so, they become participants in propaganda rather than observers of truth.