Joseph Stalin: Brutality, Mass Murder, and the Dark Reality of His Communist Rule

Stalin’s pursuit of absolute control relied on fear, propaganda and systemic violence, leaving behind one of the deadliest legacies of the twentieth century.

Total Views |

Joseph Stalin remains one of the most brutal and destructive political figures in modern history. Ruling the Soviet Union from the late 1920s until his death in 1953, Stalin exercised absolute power under the banner of Communism, leaving behind a legacy defined by terror, mass murder and systemic repression.

Rise to Absolute Power

In any recounting of Stalin’s horrific deeds, it is essential to understand how he consolidated power. After the Russian Revolution, Stalin rose through the ranks as general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the early 1920s. He later emerged as the unquestioned and de facto dictator of the Soviet Union. Once entrenched, he displayed shocking ruthlessness in suppressing dissent and killing vast numbers of his own people.

Stalin is often compared to Adolf Hitler, who orchestrated the murder of around six million Jews in the Holocaust. In the Ottoman Empire in the early twentieth century, leaders carried out the near-genocide of millions of Armenians. Millions more died as a result of Japanese war crimes during the Second World War under Prime Minister Hideki Tojo and Emperor Hirohito.

Even within the Soviet Union, Stalin’s predecessor, Vladimir Lenin, ruled with little mercy while leading a brutal revolution that claimed an estimated nine million lives.

The Gulag System

Lenin founded the GULAG, an acronym for the Main Administration of Collective Labour Camps, a network of prisons and forced labour camps spread across the Soviet Union. Stalin, however, employed this system on an unprecedented scale and with exceptional cruelty. While the camps housed criminals, their primary purpose lay in controlling the population through fear by imprisoning, torturing and killing those deemed undesirable, including critics of Communism and anyone who defied Stalin. This machinery of repression aimed to drag the Soviet Union from its agrarian past into an industrialised society.

Between 1931 and 1953, more than 3.7 million Soviet citizens were forced into these camps, many located in the most remote and barren regions of the country. Almost 800,000 of them were shot, according to one report. At its height, the GULAG comprised nearly 500 camps. More people passed through this system, and for far longer periods, than were imprisoned in Nazi Germany’s concentration camps during their entire existence.

As historian Michael Payne has observed, the purpose of the GULAG was not simply to kill people. It aimed to discipline society and functioned primarily as a mechanism of social control.

Collectivisation, Dekulakisation and Special Settlements

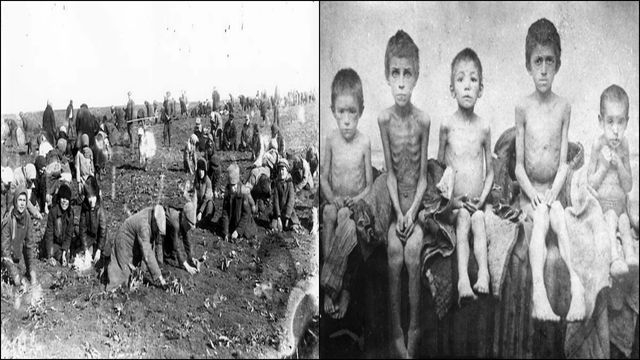

From around 1929 to 1932, Stalin pursued collectivisation in the name of strengthening Communism and tightening his grip on the state. He seized land and property from millions of peasant families and forced them from their homes, with many ending up in the GULAG.

These peasants, labelled “kulaks”, represented the wealthier segment of rural society and were viewed as a direct threat to Stalin’s authority. The regime dispossessed them, murdered many, and exiled others to collective farms or to labour camps in mining and construction. Millions more died under these conditions.

Fearing subversive elements within Soviet borders, Stalin also ordered the forced resettlement of entire populations. Authorities deported or relocated people of specific nationalities to remote regions in what became known as “special settlements”.

Through dekulakisation, Stalin effectively wiped out an entire social class. This policy inflicted severe damage on agriculture and directly contributed to mass starvation.

The Great Famine

According to The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivisation and the Terror Famine, around 14.5 million people died of starvation during the Great Famine of 1932 to 1933, also known as the Holodomor. Estimates vary widely, but historians agree that millions perished, with Ukraine and Kazakhstan suffering particularly severe losses.

Unlike other famines driven primarily by drought, this catastrophe stemmed largely from Stalin’s policies, which prioritised industrialisation over small-scale food production. Stalin also manipulated food shortages deliberately, ensuring that some regions suffered more than others. He openly welcomed many of these deaths, especially among perceived enemies of the state, kulaks and so-called idlers who did not work on collective farms. Quoting Lenin, he declared, “He who does not work, neither shall he eat.” Many scholars regard the Great Famine as an act of genocide and hold Stalin directly responsible.

Historian Norman M. Naimark, in Stalin’s Genocides, argues that while the Holocaust stands as the worst case of genocide in the modern era, the parallels between Stalin and Hitler remain impossible to ignore. Both dictators killed vast numbers of people, pursued utopian visions at the cost of human life, destroyed their societies and ultimately committed acts of genocide.

The Great Purge

In 1936, Stalin launched the Great Purge to eliminate rivals and critics within the Communist Party. The NKVD, the Soviet secret police, arrested hundreds of thousands of people. Authorities executed many or sent them to the GULAG. Of the 103 highest-ranking party officials, 81 were executed.

More than a third of the Communist Party ultimately died during the purge, which also terrorised the wider population. Many citizens informed on friends and family members in desperate attempts to avoid arrest or death. Even the head of the NKVD, Nikolai Yezhov, did not escape. The regime executed him in 1940.

Stalin also manipulated history through propaganda. He ordered photo retouchers to erase purged officials from photographs, including Yezhov, effectively removing them from the visual historical record.

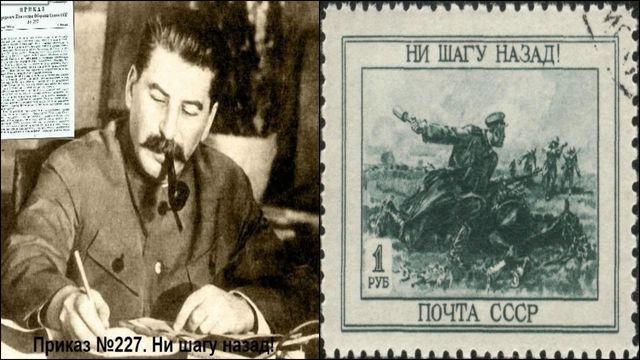

Order No. 227

Stalin’s brutality extended beyond civilians to the soldiers fighting for the Soviet Union. In 1942, as German forces advanced towards Stalingrad, he issued Order No. 227, one of his most infamous decrees. It declared that panic-mongers and cowards were to be shot on the spot.

The order also created penal battalions, sending lesser offenders to the front lines, while guard units positioned behind troops prevented retreat. The exact number of soldiers killed under this policy remains unclear.

Punishing Prisoners of War

Stalin declared, “We have no prisoners of war, only traitors of the motherland.” Unlike soldiers from other Allied nations, Soviet prisoners who survived German camps did not return home as heroes. Many underwent forced repatriation, while others remained in the West.

On their return, authorities interrogated millions of former prisoners of war. About half were sent directly to the GULAG, while thousands were executed or died in captivity at the hands of their own state.

Turning a Blind Eye to War Crimes

Although Stalin condemned perceived disloyalty among his own troops, he ignored atrocities committed by Soviet soldiers when they achieved military success. Reports of mass rape by Red Army troops in Germany and elsewhere reached him, yet he dismissed them. He reportedly remarked that a soldier who had endured such horrors might reasonably seek “fun with a woman”.

Legacy of Terror

Stalin ruled the Soviet Union with an iron grip for most of his life. When he died in 1953, the GULAG still held around 2.5 million inmates. However, both the camp system and Stalinism itself began to unravel rapidly after his death.

As Payne notes, the terror state that Stalin built collapsed quickly under his successors. One reason lay in its inefficiency. Imprisoning vast numbers of people, even as forced labourers, proved an unsustainable way to govern a nation.

Article by

Kewali Kabir Jain

Journalism Student, Makhanlal Chaturvedi National University of Journalism and Communication