Yezidi and Hindu Connection: Unveiling Ancient Spiritual Parallels

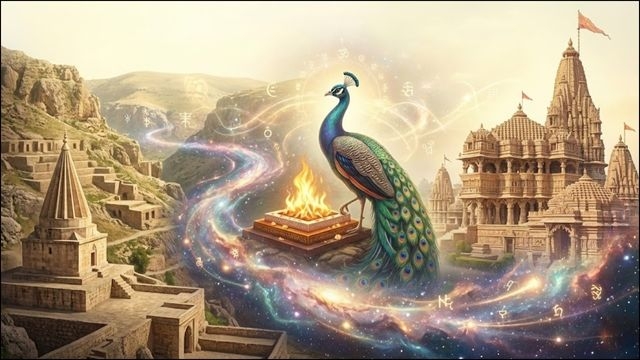

A look at the shared roots of Yezidi and Hindu traditions, showing how similar symbols, rituals and ideas point to an ancient spiritual bond.

Total Views |

Despite being separated by geography and shaped by different historical experiences, the Yezidi and Hindu traditions exhibit remarkable parallels in cosmology, symbolism and spiritual philosophy. Scholars of Indo-Iranian studies and comparative religion have long suggested that these similarities may point to a shared ancient spiritual heritage, one that predates modern religious identities and reaches back to humanity’s early civilisations.

This article explores these spiritual bridges and reveals how both traditions echo the timeless quest for cosmic harmony and divine wisdom.

1. Belief in One Supreme God and Divine Manifestations

Both Yezidis and Hindus centre their spirituality on a Supreme, Formless Creator supported by divine intermediaries.

Yezidi Theology:

God (Xwedê) is the ultimate Creator, transcendent, omnipotent and beyond human comprehension. The world is entrusted to Malakê Tawus, the Peacock Angel, who governs creation through divine light.

Hindu Philosophy:

Hindutva speaks of Brahman, the infinite formless absolute. Deities such as Vishnu, Shiva and Devi express aspects of this universal reality.

These structural similarities reflect the metaphysical ideas of ancient Indo-Iranian belief systems found in Vedic hymns and ancient Yezidi oral traditions dating back more than 3,000 years.

2. Reverence for the Peacock as a Shared Divine Symbol

The peacock, a creature of beauty, spirituality and cosmic radiance, plays a sacred role in both cultures.

Yezidis:

Malakê Tawus, the Peacock Angel, symbolises light, protection, resurrection and divine authority.

Hindus:

The peacock is associated with Kartikeya (Murugan), god of war and youth, and Saraswati, goddess of wisdom and arts.

Archaeological finds from the Indus Valley, Mesopotamia and Anatolia show similar peacock motifs, suggesting symbolic exchange along ancient trade and migration routes.

3. Cosmic Harmony and Nature Worship

Both religions emphasise living in harmony with the natural world.

Yezidi Tradition:

Festivals align with agricultural cycles. Çarşema Sor, or Red Wednesday, marks the cosmic renewal of creation.

Hindu Scriptures:

Texts such as the Rig Veda and Bhagavad Gita revere rivers, mountains, fire and earth as manifestations of divinity.

This shared eco-spiritual worldview likely originated in early agrarian societies of the Fertile Crescent and the Greater Indian subcontinent.

4. Rituals and Ancient Festivals

Festivals serve as bridges connecting communities to their ancestral memory.

Yezidi:

Çarşema Sor marks the beginning of creation. Devotees light candles at Lalish, believed to be the first place on Earth to solidify from cosmic dust.

Hindu:

Celebrations such as Diwali, Navaratri and Holi symbolise renewal, cosmic cycles and the victory of light over darkness.

Both traditions preserve some of the oldest ritual calendars in the world, possibly linked to Mithraic and Proto-Indo-European seasonal festivals.

5. Caste and Spiritual Hierarchies

Both religions historically maintained structured social orders that combined spiritual and social responsibilities.

Yezidis:

Society is divided into Sheikhs, Pirs and Murids.

Hindus:

Historically organised into four varnas, Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra.

Originally, these classifications were functional rather than discriminatory, intended to preserve ritual purity, discipline and social harmony.

6. Sacred Fire and Spiritual Energy

Fire is a central element of worship in both traditions.

Yezidis:

Candles and flame symbolise divine energy and enlightenment.

Hindutva:

Agni, the fire god, is regarded as the messenger between humans and the divine and is central to all yajnas or fire rituals.

This reflects a shared legacy of Aryan fire cults from ancient Central Asia and the second millennium BCE.

7. Oral Tradition as a Vessel of Ancient Wisdom

Both cultures relied heavily on oral transmission to preserve their sacred knowledge.

Yezidis:

Sacred hymns, known as Qewls, transmit theology, cosmology and ethics.

Hindus:

The Vedas, Upanishads and Puranas were preserved through elaborate memorisation systems for centuries before they were written down.

This oral heritage acted as a shield against invasions, displacement and forced conversions, ensuring the survival of ancient wisdom.

8. Sacred Pilgrimage Sites and Shared Symbolism

The emphasis on holy geography reflects a deep spiritual tradition.

Yezidis:

Lalish, a white-stone valley in Iraq, is their holiest site and a symbol of creation.

Hindus:

Pilgrimages to Varanasi, Rameswaram, Puri and Mount Kailash represent spiritual rebirth and liberation.

Shared symbols such as the sun, peacock, lotus and serpent appear in both traditions and reveal ancient cultural diffusion through Indo-Iranian migration corridors, Mesopotamian to Indian trade routes and Silk Road cultural exchanges.

9. Linguistic and Mythological Parallels

Several terms and mythic elements show Indo-European overlap.

The Yezidi word Xwedê resembles the Old Persian Khuda and Sanskrit Khoda or Khodaiva, all meaning God.

The concept of seven divine beings in Yezidism parallels the Sapta Rishis, or Seven Sages, and the seven Lokas in Hindu cosmology.

Both cultures share stories of cosmic eggs, world mountains and divine light beings, which hint at shared ancient myth structures.

10. Shared DNA of Indo-Iranian Heritage

Anthropologists note that both Yezidis and Hindus descend partly from ancient Indo-Iranian tribes that migrated across Central and South Asia around 1500 to 2000 BCE.

The spiritual structures of early Zoroastrianism, proto-Vedic religion and ancient Mesopotamian cults show overlapping patterns, suggesting a vast cultural super-system that stretched from the Zagros Mountains to the Indus River valley.

Conclusion: A Spiritual Bridge Across Civilisations

The Yezidi and Hindu traditions, though they evolved in different lands and historical contexts, retain deep spiritual resonances. These include belief in a supreme formless deity, reverence for nature and cosmic order, sacred fire rituals, peacock symbolism, structured spiritual communities and the oral preservation of ancient wisdom.

These parallels point toward a shared ancestral spiritual heritage that may have been forged during prehistoric Indo-Iranian migrations or even earlier within the cradle of early human civilisation.

In a world increasingly divided by identity and borders, understanding these deep ancient connections can foster mutual respect, cultural unity and a broader appreciation of humanity’s collective spiritual journey.

Article by

Adv. Alekh Sharma

Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh