On Prakruti: The Three Cultural Perspectives Towards Nature

How do different cultures understand and live with nature? Three unique stories from the West, China, and Bharat.

Total Views |

Human evolution is a complex theory that grows increasingly contradictory the more we discover clues attempting to solve mysteries about the very existence of human beings. Evolution is best understood through an anthropological perspective, for it explains how, why, and from where we have come to the stage at which we now find ourselves. It also examines the key factors associated with the categorisation of human beings into different races, cultures, and languages.

One particularly significant aspect concerns how different cultures treat nature in distinct ways. Cultural views towards nature vary widely, shaping how societies perceive, interact with, and value the natural world. These perspectives are influenced by a complex interplay of factors, including climate, geographical location, religious beliefs, and historical experiences.

At least three fundamental perspectives on humanity’s relationship with nature can be discerned, serving as points of differentiation between the Greek – Western Judeo-Christian cultural system, the Indic Hindu – Buddhist culture, and the Chinese Confucian – Taoist culture.

American political scientist Rudolph J. Rummel meticulously compares these three perspectives in Understanding Conflict and War, Vol. I: The Dynamic Psychological Field, particularly in Chapter 35: Human and Nature.

THE JUDEO–CHRISTIAN NOTION

Western philosophy has long emphasised describing and controlling nature. In classical Greek thought, nature was organismic — suffused with life and intelligence, much like the Gods of Olympus themselves. For seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Western rationalists, however, nature was conceived as a machine. Today, it is often understood in terms of probabilistic distributions of energy, with an inevitable tendency towards entropy.

In Indian philosophy, nature represents the totality of sense perceptions. In Chinese thought, it is both that which we experience and the laws or principles underlying that experience.

The Judeo – Christian tradition, however, marked a radical departure. It came to regard nature as inanimate matter to be subdued and exploited. This attitude, which has directly contributed to the ruthless abuse of the environment witnessed across the globe, can be traced to the Old Testament, particularly the Book of Genesis. On the sixth day of creation, Jehovah proclaims:

“Let us make man in our image, in our likeness, and let him rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air, over the livestock, over all the earth, and over all the creatures that move along the ground. Fill the earth and subdue it.”

Not only is man commanded to dominate, but the earth itself is mysteriously held accountable for humanity’s sins. Time and again, Jehovah unleashes his wrath upon the land:

“Say to the southern forest: This is what the Sovereign Lord says: I am about to set fire to you, and it will consume all your trees, both green and dry.”

“I will make the land of Egypt a ruin and a desolate waste among devastated lands.”

“The Lord is going to waste the earth and devastate it; he will ruin its face and scatter its inhabitants. The earth will be completely laid waste and totally plundered. Cursed is the ground because of you.”

For Western societies, this emphasis on domination has often led to the abasement and eventual atomisation of human beings themselves. Nature’s exploitation became intertwined with social exploitation, as the same principles of control applied to the physical world were extended to people. Such thinking, Rummel argues, has contributed to the crises of Western civilisation: environmental pollution, uncontrolled growth, urban disorganisation, crime, fear, and even the moral collapse embodied in fascism, Nazism, and communism.

THE SINO–TIBETAN VIEW

Chinese philosophy traditionally followed a middle path. Neither nature nor the human soul was regarded as supreme; instead, harmony between humanity and nature was paramount. Nature is seen as orderly and regular, and this same harmony should govern human relationships.

In Chinese thought, nature’s order is evident in everyday experience. Humanity is not separate from it but a unity with it. Consequently, there is no sharp distinction between subjective and objective, nor between abstract philosophy and practical life. Chinese concepts tend to be concrete rather than abstract, and philosophy itself is a way of life.

From China’s earliest dynasties, creatures both real and mythical — serpents, bovines, cicadas, dragons — were endowed with symbolic power, often depicted on ritual bronze vessels. Mountains, too, were imbued with sacred energy (qi). They drew rain for crops, concealed medicinal herbs and alchemical minerals, and symbolised gateways to other realms, such as Daoist “cave heavens” (dongtian), paradises of harmony and immortality.

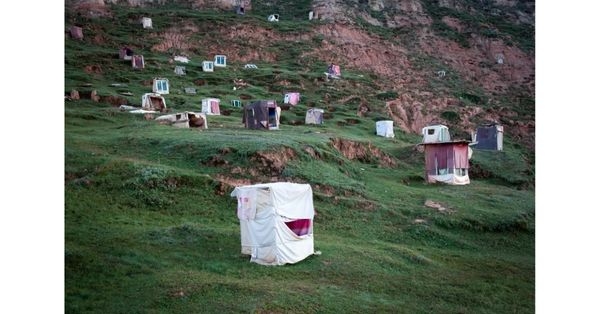

By the early centuries of the Common Era, mountains became places of spiritual renewal. Daoist and Buddhist ascetics built meditation huts and temples there, later followed by pilgrims, poets, city dwellers, and even statesmen seeking refuge in turbulent times.

Chinese philosophy’s conception of the cosmos predates formal Daoism and Confucianism but deeply influenced both. These ideas also shaped Buddhism when it entered China around the first century CE.

The natural world, in Chinese thought, is a self-generating, complex web of continuously changing and interacting elements. At the heart of this dynamic system lies the Dao (the Way). Unlike a governing deity, the Dao is not a causal force but the underlying principle uniting all things. Daoist teachings stress living in accordance with the rhythms of nature for both physical health and moral integrity.

Within this worldview, every part of existence consists of complementary forces known as yin and yang. Yin is passive, dark, secretive, weak, feminine, and cool, whereas yang is active, bright, revealed, strong, masculine, and hot. Their perpetual interaction sustains the rhythm of the universe and ensures unending transformation.

By the Han dynasty, mountains had become central motifs in art. Incense burners were shaped like mountain peaks with perforations for smoke, symbolising magical vapours. Mirrors depicted Mount Kunlun — the mythic cosmic axis — or the enthroned Queen Mother of the West. By the Tang dynasty, landscape painting had matured into a celebrated genre, expressing humanity’s deep longing to commune with nature. This tradition, alive for over a millennium, continues to inspire Chinese art today.

THE INDIC LENS

The Indic cultural perspective regards nature with a certain detachment, focusing on transcendence rather than mastery. Nature is perceived as a realm of fleeting sensations and transient forms. It is not to be dominated, exploited, or even primarily studied, but rather to be unveiled as a means to perceive the deeper reality of the Self.

What nature discloses through sensory experience is deemed untrustworthy. True knowledge comes not from the senses but through spiritual insight and receptiveness, leading to self-realisation, transformation, and ultimately release from worldly bonds. Unsurprisingly, material sciences and technologies — developments rooted in external exploration — remained comparatively underdeveloped in Bharat. Instead, Bharat prioritised the development of the soul.

As Hindutva scholar Diana L. Eck observes, the Indian subcontinent itself is conceived as a sacred geography, inseparably merging natural terrain with cultural and religious experience.

This sacredness is beautifully captured in the Bhoomi Suktam, a hymn that venerates Mother Earth:

“The Earth is upheld by Truth (Satya), Eternal Law (Ritam), Consecration (Deeksha), Devotion (Brahma), and Sacrifice (Yajna). Earth is not inert matter; she is a living mother, sustained by these virtues. Hence, humans must embody these qualities. The hymn proclaims: ‘Earth is my mother, and I am her son.’”

Hindutva does not sanction human beings to exploit the earth selfishly or anthropocentrically. Instead, it counsels balance: humans may enjoy the world, but always within limits that respect the sanctity of the earth (Nadkarni, 2008).

The philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (1973) emphasised Bharat’s immense contribution to the spiritual heritage of humanity. He observed that “half the world moves on independent foundations which Hindutva supplied” and noted how China, Japan, and many other nations continue to look to Bharat as their spiritual home.

Similarly, Nash (1989) argued that Eastern religions such as Hindutva, Buddhism, Taoism, and Zen Buddhism reject both dualism and anthropocentrism, instead affirming the ultimate oneness of all nature. By advocating immersion of the human self within a larger organic whole, these traditions paved the way for modern environmental ethics.

As Nanditha Krishna writes in Hindutva & Nature:

“Hindutva has a cosmic, rather than anthropocentric, view of the world — an ontology sharply distinct from the Abrahamic religions. Hindu traditions acknowledge that all life forms — human, animal, and plant — are equal and sacred. This worldview positions Hindutva to respond meaningfully to contemporary challenges such as deforestation, intensive animal farming, global warming, and climate change.”

Article by

Sushant S Raghuvanshi

Columnist – Writers For The Nation

Kushbhawanpur, Uttar Pradesh