The Naxal Crisis of Bharat and the UPA Government’s Denial of Taking Action

11 Oct 2025 15:20:19

Bharat has long lived under the dark shadow of Naxalism. By the mid-2000s, it had emerged as the country’s most serious internal security threat, displaying its full scale of destruction. The Union Home Ministry’s own report revealed that violence had spread across 76 districts in nine states, involving around 9,300 underground terrorists and 6,500 regular weapons. The crisis deepened not just because of the level of violence but also due to its ideological foundation, a commitment to Maoist terrorism that rejected peace and declared war against Bharat. Despite this, the government’s response remained weak and ineffective.

The Left-supported, Congress-led UPA government chose denial and inaction. The then Home Minister dismissed Naxalism as a “law and order” problem, leaving states to handle it individually, without a unified national strategy. Several political leaders and intellectuals supported peace talks, praising Andhra Pradesh’s efforts. However, the Maoists used these talks to regroup and expand into new states. Others reduced the issue to a “socio-economic problem” that could be solved through development programmes, ignoring the deeper ideological war at play.

This raises vital questions: Is Naxalism merely a law-and-order issue or an ideological conflict aimed at overthrowing the state through prolonged armed struggle? Do peace talks truly lead to reconciliation, or do they give armed groups time to rearm and spread? The answers lie in the Home Ministry’s 2004–05 report, which exposed the real scale of the Naxal threat and the government’s failure to control it.

A Threat the Government Refused to Acknowledge

The Home Ministry’s 2004-05 Annual Report painted a grim picture. Two major Naxal groups - the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) People’s War Group and the Maoist Communist Centre of India, were responsible for 91% of all Naxal violence and 89% of related deaths nationwide. Their goal was to create a “Compact Revolutionary Zone” stretching from Nepal through Bihar and Chhattisgarh down to Andhra Pradesh.

The report admitted failure, stating that “despite strenuous efforts by the security forces, there has been no let-up in the effectuation of CRZ.” Naxal groups were filling the territorial gaps in north Bihar and north Chhattisgarh to link their strongholds across multiple states. Yet, the Union government continued to treat the crisis as a state-level problem. This fragmented approach allowed extremists to move freely across borders while individual states struggled without central coordination.

The Deadly Merger That Changed Everything

In October 2004, two of Bharat’s most violent Naxal outfits merged to form the Communist Party of India (Maoist). This was a turning point, creating a single command structure with thousands of trained terrorists. Despite recognising this, the government failed to respond with urgency. The Home Ministry report noted the merger but offered no new counter-strategy.

Violence rose sharply during the UPA government’s tenure. In Bihar, Naxal incidents increased by 29% and deaths by 34%, mainly due to growing aggression by the People’s War Group. Jharkhand recorded a 44% rise in Naxal-related deaths in 2004 compared to 2003. In Chhattisgarh, attacks on police intensified. The report confirmed that in Jharkhand alone, 41 policemen were killed in concerted Naxalite assaults.

The Peace Talks Trap

One of the period’s biggest mistakes was holding peace talks with Naxal groups, especially in Andhra Pradesh. The People’s War Group and the state government declared a three-month ceasefire starting June 2004. The first round of direct talks concluded in October the same year.

The ceasefire, however, proved disastrous. Instead of pursuing peace, the Maoists regrouped, recruited and rearmed. On 17 January 2005, they withdrew from the talks, alleging killings of their cadres. By then, they had strengthened their presence. The Home Ministry acknowledged that despite peace efforts, “the overall quantum of Naxals remained more or less at the same level.”

During the talks, Naxal violence rose by 15% in Maharashtra. The groups expanded into Odisha, West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh. The CPM-led government in West Bengal criticised the peace talks, warning that hiding in jungles and launching attacks could never bring social change. They insisted that talks could only proceed if Maoists laid down their weapons and accepted the Constitution.

Not Poverty, But Ideology

Analysts who explained Naxalism as a socio-economic problem misunderstood its nature. The Maoists’ own strategy document, Strategy and Tactics of the Indian Revolution (2004), made their intentions clear: “The central task of the Indian revolution is the seizure of political power.” It called for the destruction of the Bharatiya state through armed warfare.

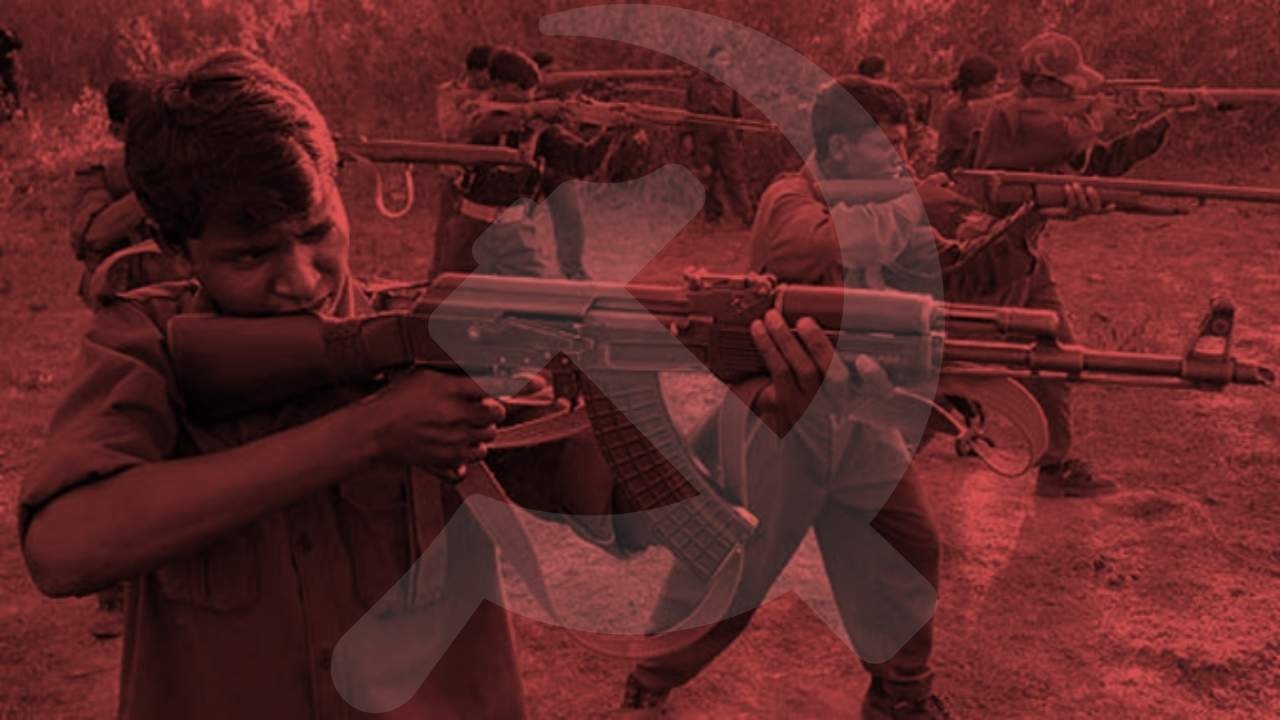

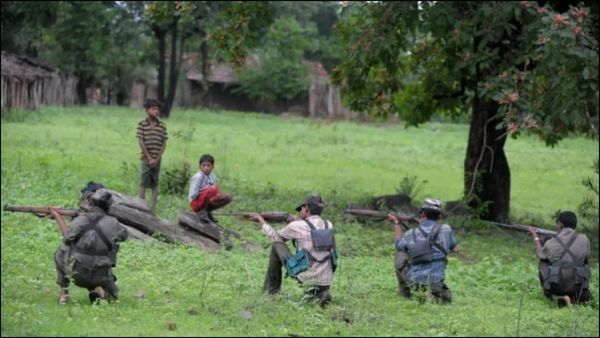

Their objective was not development but total state control through guerrilla war. The Home Ministry described their tactics, “Jan Adalats, targeted attacks on police, political leaders and public property, coupled with militarisation and tactical upgrades.” These Jan Adalats were not courts but execution grounds where villagers were killed before their families. Schools, roads and development projects were destroyed to keep regions under Maoist control.

The Cross-Border Connection

The Naxal movement was not confined within Bharat’s borders. The Home Ministry reported growing ties between Indian Maoists and Nepal’s Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist). The groups exchanged arms, manpower and training, with Nepalese cadres visiting Naxal camps in Jharkhand and Bihar.

CPN-M cadres also took refuge in cities like Siliguri and Patna. Despite being banned as a terrorist organisation under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Amendment Act, 2004, the CPN-M played a key role in uniting India’s two largest Maoist outfits into CPI (Maoist). This transformed the issue from an internal insurgency into a regional terrorist network with shared ideology and strategy.

A Government in Denial

Despite overwhelming evidence, the government failed to respond effectively. The Home Ministry acknowledged that Naxalism “continues to remain a cause of concern” but offered no decisive policy. The fragmented, defensive approach remained unchanged. There was no recognition that this was an ideological war, not just a law-and-order problem.

Instead, the UPA government continued to treat Maoist terrorism as a protest movement open to negotiation. This misjudgement cost thousands of lives.

The Cost of Inaction

The price of this denial was immense. Thousands of security personnel and civilians were killed. Schools, hospitals, roads and bridges were destroyed. Entire regions were held hostage by armed terrorists who rejected democracy and the Constitution.

The Home Ministry documented the Naxals’ growing arsenal of unlicensed weapons, landmines and improvised explosive devices. These were used in systematic, ideologically driven attacks.

The massacres at Ranibodli in 2007, where 55 policemen were killed, and Tadmetla in 2010, where 76 CRPF jawans died, highlighted the scale of failure. These were not battles but mass killings.

In contrast, today’s government has adopted a dual approach, combining strong security operations with rapid development. Roads, schools, electricity and healthcare facilities are reaching former Maoist strongholds. Over 400 Maoists have surrendered, and Naxal-affected districts have reduced sharply. The Home Minister has set a clear national goal to eliminate Naxalism by 2026.

Conclusion

The events of 2004–05 remain a warning of what happens when a government fails to recognise the true nature of a threat. The Home Ministry’s report exposed the scale of the Naxal menace, yet the UPA government failed to act with unity or conviction. It treated an armed insurgency as a socio-economic issue and allowed peace talks to become cover for Maoist expansion.

The lessons from that failure are now clear. Naxalism is not a law-and-order or poverty issue; it is an ideological war to seize power through violence. Peace talks without disarmament only help these terrorists regroup, and development without security is futile.

The mistakes of 2004–05 cost thousands of lives, but they reshaped Bharat’s strategy. The current approach, firm security action, rapid development and zero tolerance for armed groups, has yielded visible success. The once-feared Red Corridor, which spanned 165 districts in 2005, has now shrunk to a few isolated pockets.

Bharat has learnt a painful truth: "Peace is not achieved through retreat, but through resolve!"

Article by

Aadarsh Gupta

Young Researcher