Sundar & Varadarajan: The Elite Face of India’s Red Narrative

As India confronts multiple fronts—from border threats to internal insurgency, from digital disinformation to cultural erasure—it must recognize that the enemy is not always armed. Sometimes, the most potent adversaries are those who come cloaked in academic robes and journalistic credentials, speaking the language of rights while enabling violence.

In a political landscape marked by insurgencies, ideological warfare, and foreign influence, the intersection of academia, activism, and journalism has often played a critical role—sometimes as a force for justice, other times as a vehicle for destabilization.

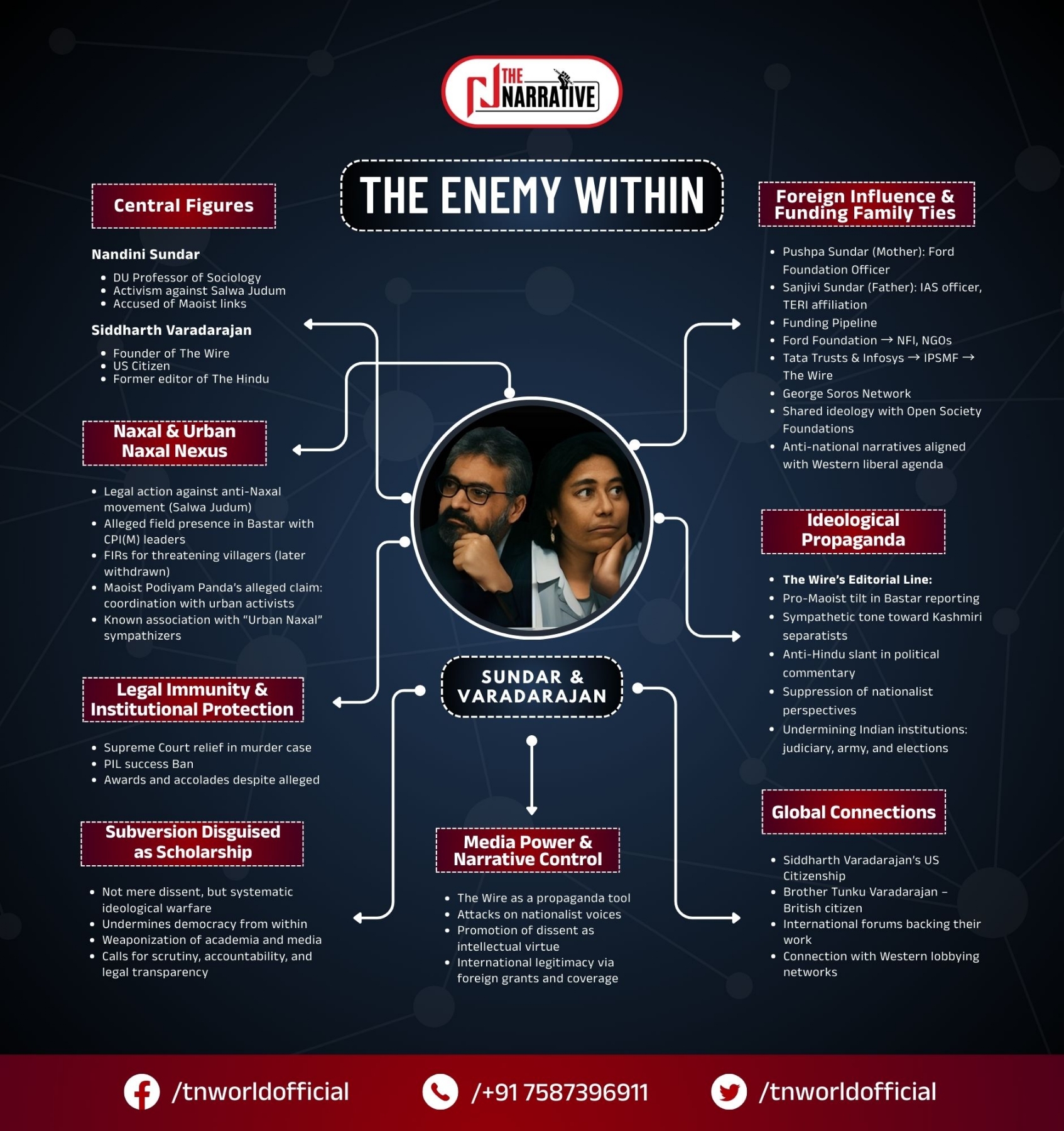

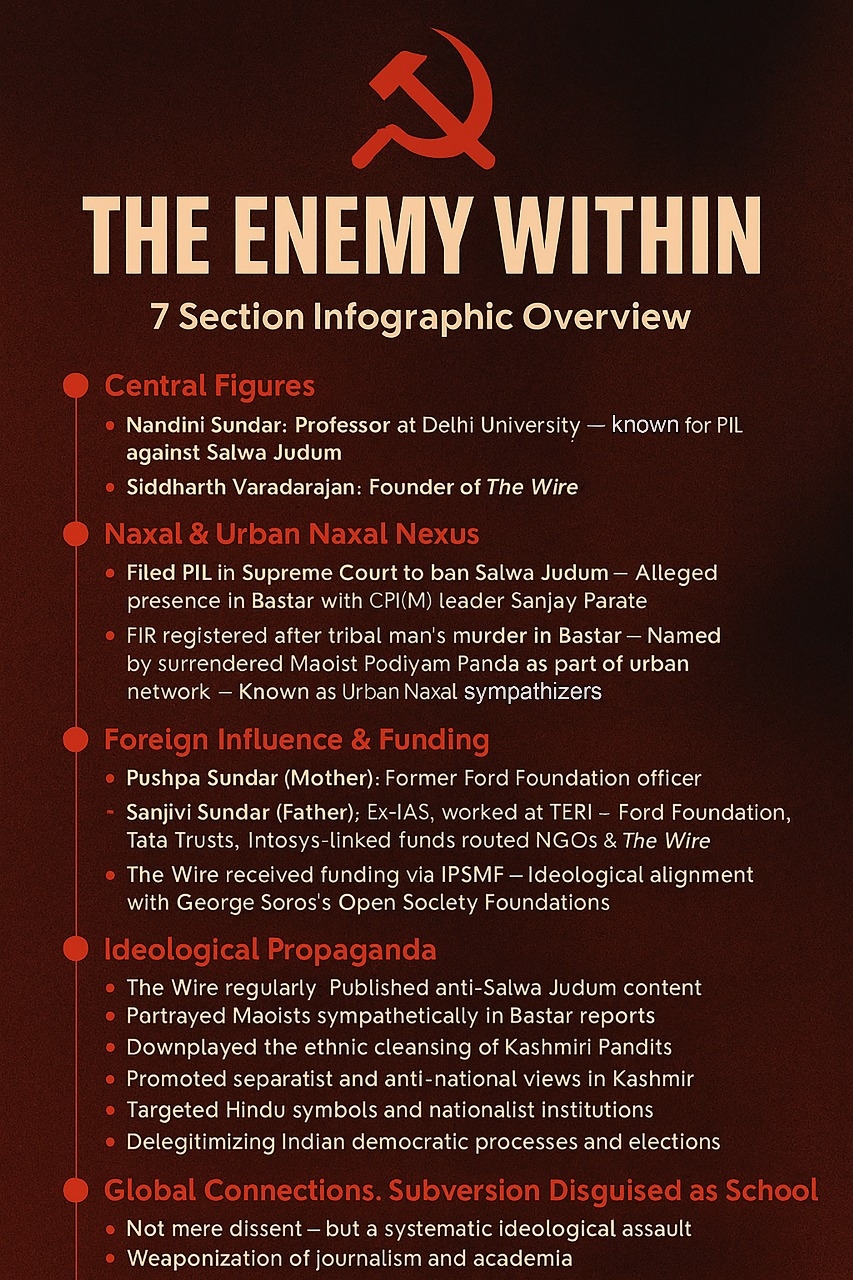

Among the figures consistently at the center of this volatile convergence stand Nandini Sundar, a Marxist professor of Sociology at Delhi University, and her husband Siddharth Varadarajan, founding editor of the now-banned website The Wire, which has been under scrutiny for its Marxist-leaning, anti-India reporting.

Together, they represent a powerful and deeply entrenched elite that has, over decades, embedded itself within academia, media, and international philanthropic networks. Their public profiles may project the image of liberal intellectuals advocating for human rights and press freedom, but beneath this progressive veneer lies a far murkier nexus.

The origins of this duo’s ideological convictions can be traced not just to their own personal inclinations, but to the institutional, familial, and global frameworks that have nurtured them. Nandini Sundar is the daughter of Pushpa Sundar and Sanjivi Sundar, both are IAS of 1963 batch who took early retirement but remained active in the world of NGOs and corporate-funded civil society.

Her mother, Pushpa Sundar, later became a program officer at the Ford Foundation, an institution that has been repeatedly criticized for its attempts to reshape domestic policies in the Global South under the garb of development.

Not content with bureaucratic service, Pushpa Sundar went on to establish the National Foundation for India (NFI) and Sampradaan, organizations that claimed to promote philanthropy but increasingly aligned themselves with anti-establishment, and often anti-national, voices.

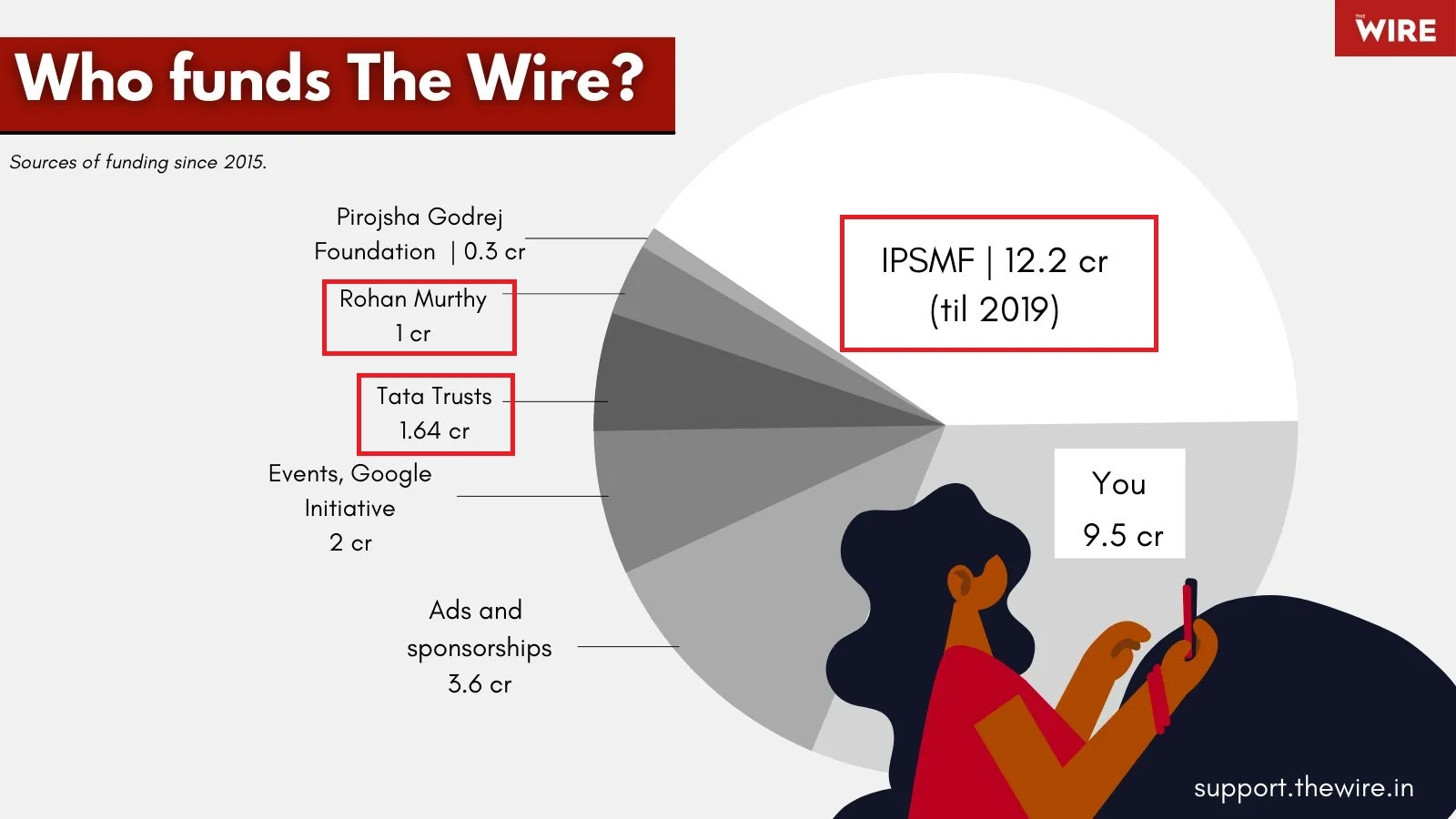

It is no coincidence that the same Ford Foundation, along with the Tata Trusts and Infosys-linked bodies, have been the backbone funders of media institutions such as The Wire.

Between them, these entities have poured in crores of rupees under the banner of “independent journalism,” a euphemism that in this context masks an unrelenting ideological onslaught on the Indian state, its democratic institutions, and its civilizational identity.

That Ratan Tata, one of India’s most respected industrialists, served as a Ford Foundation trustee, and that Narayan Murthy did the same between 2008 and 2014, is more than a footnote—it is a case study in how elite networks sustain dissent not as democratic participation, but as intellectual sabotage.

The Tata Trusts and Infosys-linked bodies would later become major donors to the Independent and Public-Spirited Media Foundation (IPSMF), which funds The Wire.

Siddharth Varadarajan, though operating in a seemingly different field, completes the circle. A naturalized U.S. citizen, reportedly by birth due to a deliberate act of “birth tourism” by his parents, Siddharth never renounced his foreign nationality even as he ran one of India’s most influential news platforms.

His father, Muthusamy Varadarajan, was a senior IAS officer, who served in high-ranking positions including as minister at the Indian High Commission in London. The senior Varadarajan was known for ordering police firing during civil unrest—a fact rarely discussed, and never condemned, by his so-called activist son.

Meanwhile, Siddharth’s brother, Tunku Varadarajan, holds British citizenship and functions as a mouthpiece for left-liberal discourse in Western journals. This is a family steeped not just in privilege but in transnational ideologies, untethered from the grassroots realities of Bharat.

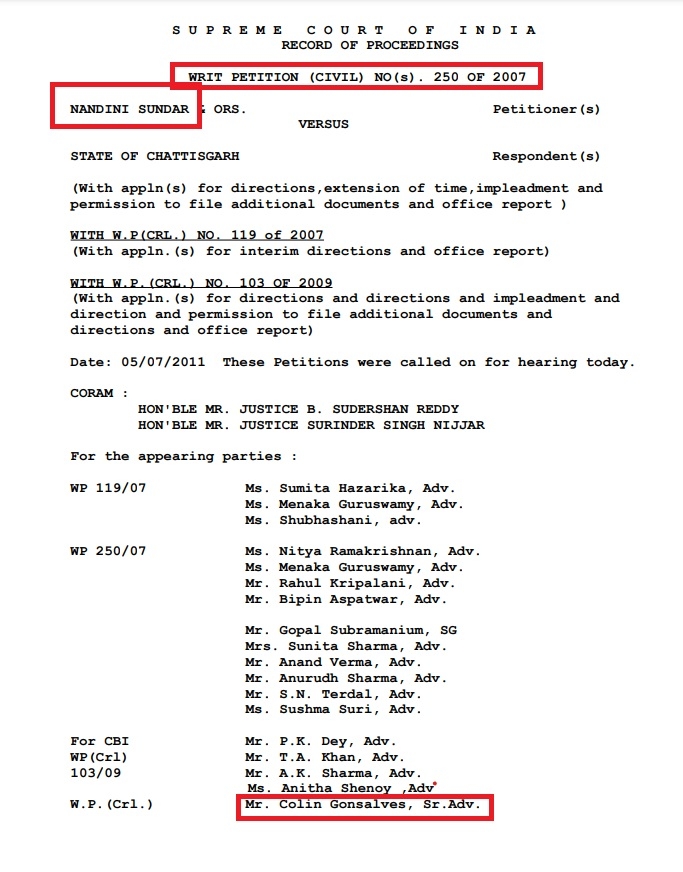

On the other side, to understand the political significance of Nandini Sundar’s activism, one must revisit 2007, when she filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court challenging Salwa Judum, a civilian militia raised to counter Maoist insurgents in Chhattisgarh. The movement, founded by tribal leader and Congress MLA Mahendra Karma, had achieved localized success by mobilizing tribal youth against Naxal terror.

In the mid-2000s, Salwa Judum emerged in Chhattisgarh as a rare example of tribal-led resistance against the Maoist insurgency. Spearheaded by Congress leader Mahendra Karma, it drew from tribal populations who were tired of living under Naxal terror.

Nandini Sundar filed a PIL in the Supreme Court demanding a ban on Salwa Judum, arguing that it violated human rights. Represented by Colin Gonsalves, a known leftist legal activist, she won the case in 2011. That judgment effectively crippled local resistance against Maoists.

Just two years later, Mahendra Karma, the tribal leader who embodied that resistance, was brutally assassinated by Maoists—stabbed seventy-eight times. This was not mere symbolism. It was annihilation.

In 2016, Sundar visited Bastar under the fake identity of “Richa Keshav,” accompanied by CPI(M) leader Sanjay Parate. Shortly thereafter, Shamnath Baghel, a local tribal who resisted Maoist threats, was murdered. His wife initially named Sundar and her associates in the FIR. Though charges were later withdrawn, likely due to pressure or fear, the circumstantial pattern remains damning.

Adding to the intrigue is the surrender of Podiyam Panda, a former Maoist and sarpanch from Sukma, who stated on record that he had facilitated visits of urban activists—including Nandini Sundar and Bela Bhatia—into Maoist territory. His public confession was quickly discredited by Sundar and her allies as “coerced,” yet the broader pattern of engagement, where academics double as interlocutors for armed insurrectionists, remains unaddressed.

While Sundar operated under the aegis of “research” and “fieldwork,” Siddharth Varadarajan constructed the ideological fortress known as The Wire. In the name of independent journalism, The Wire consistently published content that questioned the integrity of Indian elections, dismissed the horrors of Maoist and Islamist violence, and created an echo chamber that justified secessionist thought.

Its coverage of Kashmir was particularly egregious—whitewashing the ethnic cleansing of Kashmiri Pandits, glorifying stone-pelters, and amplifying foreign-sponsored voices that likened Indian democracy to military occupation.

The Bastar narrative on The Wire was no different. The Maoist atrocities that destroyed lives, recruited children, and executed dissenters were downplayed.

Instead, the platform targeted Indian security forces, painted the state as a colonial oppressor, and hailed those aligned with insurgent thought as human rights defenders.

Such propaganda, financed by institutions that answer to George Soros, Open Society Foundations, and their ideological progeny, was anything but spontaneous.

Soros has publicly stated that he aims to bring down nationalist governments globally. The alignment between his mission and The Wire’s editorial stance is more than coincidental—it is structural.

The funding trails, the ideological overlap, and the mutual disdain for India’s political evolution under a democratically elected government all point to a coordinated, if covert, campaign to delegitimize the Indian nation-state.

What makes this dangerous is not just the content of their views, but the immunity and intellectual cover they enjoy. When charges are filed, they are dismissed as politically motivated. When funding is exposed, it is defended as a commitment to free speech. When ideology is challenged, it is masked under academic freedom. In reality, what we are witnessing is not dissent—it is infiltration. Not journalism, but subversion.

The tragedy is that such individuals, born into bureaucratic privilege, educated in elite institutions, and protected by international awards and fellowships, have become the very instruments of the civilizational attack on India.

As India confronts multiple fronts—from border threats to internal insurgency, from digital disinformation to cultural erasure—it must recognize that the enemy is not always armed. Sometimes, the most potent adversaries are those who come cloaked in academic robes and journalistic credentials, speaking the language of rights while enabling violence.

The stories of Nandini Sundar and Siddharth Varadarajan are not stories of dissent. They are cautionary tales of how entrenched privilege, global funding, and ideological fanaticism can coalesce to challenge the very foundations of national unity.

In exposing them, India is not curbing free speech. It is reclaiming its narrative. It is asserting that freedom cannot be a trojan horse for anarchy. And that those who thrive on the benevolence of the very state they seek to dismantle cannot do so without scrutiny, consequence, and the full weight of democratic accountability.