Cautious Tiger, Aggressive Dragon?

India and China remain locked in a tense rivalry over unresolved border disputes, particularly along the Himalayas. IPS Officer Akun Sabharwal analyzes the historical roots, China"s strategy, and India"s response.

India and China, geopolitical rivals, face each other over a disputed 4057-km border without a mutually agreed line of control. Both countries seek to play a pivotal global role by redalming the glory they enjoyed before they went into decline from the 18th century onward due to the colonialists. Even though neither country is in a position to dominate the other, yet each views the other as a rival. Although they have different histories, identities, and cultures and represent competing political and social models of development, the fluid relationship between them has an important bearing on Asian geopolitics, international security, and globalization.

China and India are comparatively speaking new neighbors. The huge Tibetan plateau separated the two civilizations, thereby limiting Interaction to sporadic cultural and religious contacts, with no political relations. It was only after Tibet's annexation in 1951 that the Han Chinese first appeared on India's Himalayan frontiers. The month-long 1962 war, ending in China's triumph, sowed the seeds of rivalry.

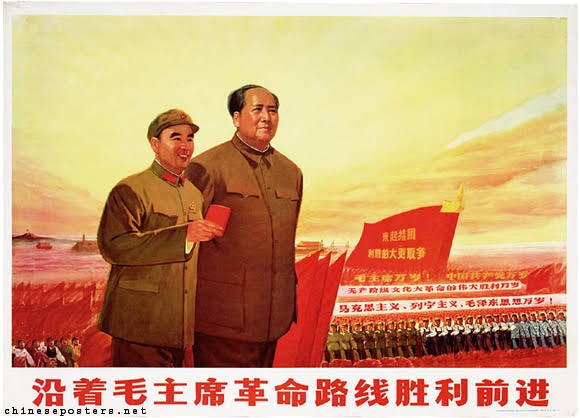

Ironically, after the Communists came to power in China in 1949, India was one of the first countries to embrace the Mao Zedong-led regime. Yet in one of his first actions after seizing power, Mao confided to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin that Chinese forces were "preparing for an attack on Tibet" and inquired whether the Soviet Air Force could help transport suppiles. Even as China annexed Tibet, India continued to court it, seeing it as a benign neighbor. It even opposed a discussion in the United Nations, in November 1950, on the then-independent Tibet's appeal for International help against Chinese aggression.

Nehru was taken largely unawares by the Chinese military attack on Tibet in October 1950 when the global attention was focused on the Korean War. He later admitted that he had not anticipated the callousness with which China took over Tibet. His strategic naivetë is proven by a note, dated July 1949 "Whatever may be the ultimate fate of Tibet in relation to China, I think there is practically no chance of any military danger to India arising from any change in Tibet. Geographically, this is very difficult and practically it would be a foolish adventure." What he credulously saw as a "foolish adventure" was mounted within a matter of months.

Nehru, the incorrigible idealist, even rejected the U.S. and Soviet proposal that India take China's vacant seat in the United Nations Security Council "Informally, suggestions have been made by the U.S. that China should be taken into the UN but not in the Security Council and that India should take her place in the Council, We cannot, of course, accept this."

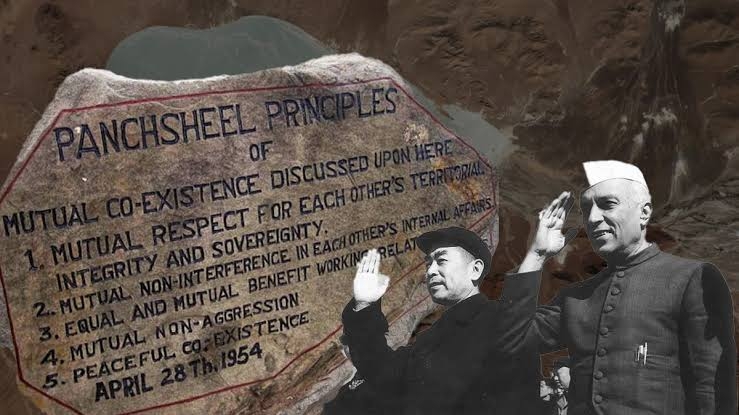

The largely one-sided "Panchsheel" incorporated a formal Indian recognition of the new Chinese control over Tibet, forfeiting all the extraterritorial rights and privileges it had enjoyed in Tibet. India agreed to withdraw its military escorts stationed at Yatung and Gyantse and to hand over the postal, telegraph and public telephone services operated by India in Tibet.

India's formal acceptance of the Chinese claim over Tibet came without extracting a reciprocal Chinese acceptance of the then prevailing Indo-Tibetan border, Including the McMahon line. In fact, no sooner had the Panchsheel Agreement been signed than China lald claim to Indian areas. Before long, it began building a highway through India's Ladakh region to link Tibet with Xinjiang.

In the years after the Panchsheel Agreement, Sino-Indian relations became tense with Chinese cross-border encroachments culminating in a full-fledged Chinese military attack in 1962. Just as Mao began his invasion of Tibet while the world was occupled with the Korean War, he chose a perfect time for invading India: the beginning of the attack coincided with the deployment of Soviet missiles in Cuba. China's unilateral ceasefire also coincided with America's termination of Cuba's quarantine.

India did not restore diplomatic relations with China, broken by the 1962 war, until after Mao's death in 1976. In 1981, India and China agreed to open negotiations on finding ways to resolve their border disputes. More than four decades later, these negotiations are still continuing, with little progress in settling the disputes. The two sides have signed three vaunted border-related accords:

1) 1993 agreement to maintain "peace and tranquility along the Line of Actual Control" (although there is no mutually agreed line of control, let alone an actual line of control);

2) 1996 accord on "confidence- building measures in the military field"; and

3) 2005 agreement identifying six "guiding principles" for a settlement of the frontier disputes. However, Immediately after this, Beijing claimed additional Indian areas.

Inspite of the fact that in recent years, the border talks have expanded into an all-encompassing strategic dialogue, the negotiations stand deadlocked. Yet neither side wants to abandon the apparently fruitless process.

In the last 30 years, with its rapidly accumulating military and economic power, China has emerged as a rising power in the making. The longer the negotiating process continues without yielding results, the greater the opportunity Beijing will have to mount strategic pressure on India and leverage its position. It alreally holds the military advantage on the ground as its forces control the majority of the heights. Furthermore, by building railroads, airports, and highways in Tibet, It is in a position to move additional forces to the border rapidly, potentially giving it the ability to strike at India at a time of its choosing.

Diplomatically, China is a contented party, having occupied the Aksal Chin plateau which provides the only accessible Tibet-Xinjiang route through the Karakoram passes. Yet China chooses to press claims on additional Indian territories, arguably as part of a grand strategy to gain leverage in bilateral relations and, more Importantly, to keep India under military and diplomatic pressure.

At the core of China's strategy is an apparent resolve to hold off indefinitely on a border settlement with India through an overt refusal to accept the territorial status quo. In not hiding its intent to further redraw the Himalayan frontiers, Beijing only helps highlight the futility of the ongoing process of political negotiations.

The territorial status quo can be changed, on the scale sought by China, not by talks but by further military conquest. Yet, paradoxically, the political process remains important both for Beijing and New Delhi to provide the façade of bilateral engagement.

China's assertive resurrection of its claims to Arunachal Pradesh in recent years could undermine this façade. Since 2006, China has publicly raked up the issue of Arunachal Pradesh, which it claims largely as its own on the basis of alleged Tibetan ecclesial or tutelary links to them, not to any professed Han Chinese links. China originally fashioned its claim to Arunachal Pradesh as a bargaining chip to compel India to recognize its occupation of the Aksai Chin plateau. For this reason, It withdrew from Arunachal in 1962, but retained its territorial gains in Aksal Chin. It's more recent resurrection of its long-dormant claim to Arunachal Pradesh has largely coincided with Beijing eyeing the state's rich water resources.

The resurrected claim to Arunachal Pradesh is linked with Beijing's successful strategy of getting India to accept gradually Tibet as part of China. Whatever leverage India still had on the Tibet issue was surrendered in 2003 when it shifted its position from Tibet being an "autonomous" region within China to it being "part of the territory of the People's Republic of China." A

However, despite the cross-border incursions and tensions, China and India have, till recently, consciously sought to downplay the border friction and instead put emphasis on their fast-growing trade. This focus on trade, even as political disputes fester, plays Into the Chinese agenda to secure new markets in India while continuing with a strategy to contain that country within the South Asian region. So, even as China has emerged as India's largest trading partner, the Sino-Indian strategic dissonance and border disputes have become more pronounced. New Delhi has sought to retaliate against Beijing's growing antagonism by banning Chinese goods and software. But such modest trade actions can do little to persuade Beijing to abandon its moves to encircle and squeeze India strategically by employing China's rising clout in Pakistan, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal.

New Delhi's warming relationship with Washington has only emboldened Beijing to up the ante through border provocations, resurrection of its claim to Arunachal Pradesh, and other diplomatic needling. Beijing had initially sought to Improve ties with New Delhi so that it could dissuade it from moving closer to Washington. But, of late, China appears to have adopted a more coercive policy, even adopting a type of psychological warfare. It is employing its state-run media and nationalistic websites to warn of another armed conflict berating India for "recklessness and arrogance."

China, which occupies one-fifth of Kashmir, has a three-pronged policy to build pressure on New Delhi over Kashmir. It has enlarged its footprint in Pakistani-occupied Kashmir through strategic projects and PLA deployment there: It has attempted to question India's sovereignty over Kashmir, and it has officially shortened the length of the Himalayan border it shares with India by eliminating the 1,597 km line along Chinese-held Kashmir.

As a result of the renewed tensions, the India-China frontier has become more "hot" than the India-Pakistan border, but without rival troops trading fire. Indeed, Sino-Indian border tensions now are the most serious since the 1962 war and 1986-87 military skirmishes that were triggered by the PLA moving south in Sumdorong Chu sector in Arunachal. Today, the PLA's forays Into Indian territory are occurring even in the areas where Beijing earlier did not dispute the frontiers.

In response, India has been beefing up its defensive deployments in Aunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, and Ladakh to prevent any Chinese land-grab. It also has launched a crash program to improve its logistical capabilities through new roads, airstrips, and advanced landing stations along the Himalayas. None of these steps, however, can materially alter the fact that China holds the military advantage on the ground.

The most Important question relates to China's intentions. In muscling up to India, is China seeking to intimidate India or actually fashioning an option to wage war? The present situation, in several key aspects, is similar to the one that prevailed in the run-up to the 1962 invasion of India.

Like in the pre-1962 war period, it has become commonplace internationally to speak of India and China in the same breadth. The aim of "Mao's India war" in 1962 was political: To cut India down to size by demolishing what it represented-a democratic alternative to the Chinese autocracy. The swiftness and force with which Mao defeated India helped discredit the Indian model, boost China's international Image and consolidate Mao's internal power. The return of the China India pairing decades later is something Beijing viscerally detests.

Just as the Dalai Lama's flight to India in 1959-and the ready sanctuary he got here set the stage for the Chinese military attack, the exlled Tibetan leader, more than 60 years after his escape, stands as a bigger challenge than ever for China, as underscored by Beijing's stepped-up vilification campaign against him. The Dalal Lama's failing health and the fight over a successor, in the future, may lead to "consequences."

The present pattern of cross-frontier incursions and other border Incidents as well as new force deployments and mutual recriminations is redolent of the situation that prevalled before the 1962 war. When in 1950, the PLA occupled the then-Independent Tibet and nibbled at Indian territories, this was not termed as expansionist. But when the Indian Army belatedly sought to set up posts to stop further Chinese encroachments, Beijing dubbed it a provocative "forward policy." In the same vein, the present Indian efforts to beef up defenses in the face of growing PLA cross-border forays are being labeled "new forward policy."

Just as India had retreated to a defensive position in the border negations with Beijing in the early 1960s after having undermined its leverage through a formal acceptance of the "Tibet region of China, New Delhi similarly has been left in the unenviable position today of having to fend off ever greater Chinese territorial demands. Little surprise, therefore, the spotlight now is on China's Tibet-linked claim to Arunachal Pradesh rather than on Tibet's status itself.

Against this geopolitical background, India can expect no respite from Chinese pressure. Whether Beijing actually sets out to teach India "the final lesson" by launching a 1962-style surprise war will depend on several factors, including India's defense preparedness to repel such an attack, domestic factors within China-such as economic and social unrest threatening the Communist hold on power and the availability of a propitious International timing of the type the Cuban missile crisis had provided in 1962. But if India is not to be caught napping again, it has to inject greater realism into its China policy and shoring up its deterrent capabilities.

Article by

Akun Sabharwal

Indian Police Service

Former IG, NE Frontier, ITBP