How Mamata Banerjee’s Government Held National Security Hostage for Nearly a Decade

Despite funds, approvals and paid compensation, Mamata Banerjee’s regime blocked fencing work, turning West Bengal’s border into a security liability.

Total Views |

In a stinging indictment of administrative apathy with grave national security implications, the Calcutta High Court on 27 January 2026 directed the Mamata Banerjee led West Bengal government to hand over already acquired land to the Border Security Force (BSF) for Indo–Bangladesh border fencing by 31 March 2026. The judicial intervention marks a decisive moment in a dispute that has dragged on since 2016, despite repeated Cabinet approvals, central funding, and mounting security warnings. The High Court’s order makes the position unequivocally clear: national security cannot remain hostage to political delay, bureaucratic inertia, or electoral considerations.

A Porous Border and a Prolonged Failure

The Indo–Bangladesh border, spanning 4,096 kilometres, ranks among Bharat’s most sensitive and vulnerable international frontiers. West Bengal alone accounts for 2,216 kilometres, which is more than half of the entire border length. Yet nearly 26% of this stretch remains unfenced, turning the region into a hub for infiltration, cattle smuggling, drug trafficking, human trafficking, and the circulation of counterfeit currency.

Since 2016, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs has repeatedly approved and funded land acquisition for fencing across nine border districts: Cooch Behar, Jalpaiguri, Uttar Dinajpur, Dakshin Dinajpur, Maldah, Murshidabad, Nadia, North 24 Parganas, and South 24 Parganas. The total critical stretch identified for fencing measured approximately 235 kilometres.

However, nearly a decade later, the state government has handed over only about 71 kilometres of land to the BSF.

This glaring gap between approval and execution lies at the heart of the controversy and now stands at the centre of judicial scrutiny.

Centre Versus State: Constitutional Duties Ignored

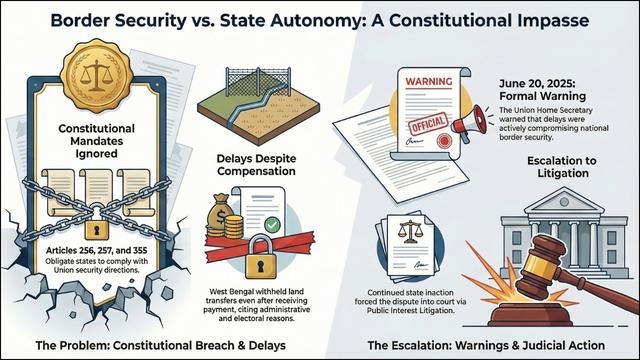

Land acquisition falls under the State List, Entry 23, but when matters of national defence and external security arise, the Constitution leaves little scope for ambiguity. Articles 256, 257, and 355 obligate states to comply with Union directions and to ensure protection against external aggression.

Despite these clear constitutional mandates, the West Bengal government repeatedly delayed the transfer of land even in cases where compensation had already been paid. The state cited administrative procedures, its Direct Purchase Policy, electoral roll revisions, and impending Assembly elections as reasons for inaction.

In contrast, the Centre issued multiple reminders. A key letter dated 20 June 2025 from the Union Home Secretary to the West Bengal Chief Secretary urged immediate compliance and warned that continued delays were compromising border security. The state administration ignored these warnings, ultimately forcing the issue into the judiciary through a Public Interest Litigation.

The PIL That Exposed Systemic Negligence

The Public Interest Litigation titled Lt. Gen. Dr. Subrata Saha v Union of India and Others (WPA(P)/450/2025) laid bare the scale of the state government’s inaction. The petitioner, a former senior Army officer, argued that unfenced borders posed a direct threat to Bharat’s sovereignty and internal security.

Relying on parliamentary records and official data, the petition demonstrated how smugglers and infiltrators continued to exploit gaps in fencing while the state government sat on land that it had already acquired. The petitioner asserted that border fencing did not constitute a routine infrastructure project but rather a core issue of national defence and territorial integrity.

The Court found substance in these arguments, particularly noting the inexplicable delay since 2016 despite the release of funds and the completion of legal acquisition processes.

What the Data Reveals

By August 2025, official data presented a stark picture of the logistical challenges along the Indo–Bangladesh border in West Bengal. Out of a total border length of 2,216.7 kilometres, authorities had fenced only 1,647.7 kilometres, leaving a substantial gap of 569 kilometres. While a small portion of this gap, amounting to 112.78 kilometres, is considered physically non feasible due to riverine terrain or geographical constraints, the remaining 456.22 kilometres remains technically feasible.

Yet this feasible stretch continues to face delays primarily due to administrative failures and unresolved land related issues.

The data further reveals that the principal obstacle does not stem from a lack of central initiative but from failures in the land acquisition and transfer process managed at the state level. Of the pending stretches, authorities handed over land for only 77.9 kilometres. Administrative inertia becomes evident in the 378.29 kilometres where acquisition remains incomplete and the 148.97 kilometres where the process has not even begun. Most strikingly, for 181.63 kilometres, the government has already made payment, yet the state administration has still failed to hand over possession for fencing.

The High Court Steps In

A Division Bench headed by Chief Justice Sujoy Paul and Justice Partha Sarathi Sen refused to accept what it described as procedural excuses. During earlier hearings, the Court questioned why the state had not transferred land for which full compensation had already been paid. The Bench also asked why authorities never invoked Section 40 of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, which provides for urgent acquisition in cases involving national defence.

On 27 January 2026, the Bench delivered its strongest directive yet. It ordered that all land already acquired and paid for must be handed over to the BSF by 31 March 2026. The Court also ruled that electoral roll revision and upcoming elections cannot serve as impediments and that national security obligations override administrative convenience. The matter now stands listed for review in April 2026 to ensure compliance.

State’s Defence Falls Flat

The West Bengal government attempted to justify its delays by invoking its Direct Purchase Policy. It argued that standard procedures under the 2013 land acquisition law must apply and that Section 40 constitutes an exception reserved for extreme emergencies.

The Court rejected this reasoning. It observed that the Direct Purchase Policy aims to address stalled development projects and does not apply to securing international borders. In cases where the government had already acquired land and paid compensation, the Bench held that no justification existed for withholding possession from the Border Security Force.

A Judicial Indictment with National Implications

The High Court’s ruling extends beyond a procedural directive. It stands as a sharp judicial indictment of a decade long failure that left Bharat’s eastern frontier vulnerable. By compelling the state government to act, the judiciary reaffirmed that political calculations cannot supersede national defence.

With the 31 March 2026 deadline approaching, the order represents a crucial test of constitutional responsibility for the West Bengal government. Compliance would finally allow long delayed fencing work to move forward, strengthen surveillance, curb illegal activities, and restore confidence among border communities and security personnel alike.

Written by

Kewali Kabir Jain

Journalism Student, Makhanlal Chaturvedi National University of Journalism and Communication