The Decline of Indian Industries Under the Shadow of Communist Trade Unions: Case Studies from Kanpur and Modinagar

25 Jul 2025 12:09:35

Trade and labour unions in India, ruled by the Marxist ideology, have significantly disrupted industries and deterred investment. From violent labour strikes in West Bengal and Kerala to operational shutdowns of iconic industries in Northern India, where their tragic influence has repeatedly caused economic instability. This has led to job losses and hurt local businesses while benefiting foreign companies. Many Indian companies have been forced to relocate operations to avoid the stranglehold of militant unionism.

The role of trade unions, especially those affiliated with communist ideologies, has played a vicious role in the politicisation of the employment of the poor. Which have brought inflexible tactics in sectors that have served as the economic lifeline to India, which not only cripple large industries but also pose a threat to the growth of the Indian economy.

Reflecting on the history of trade unions in Northern India, they have been a havoc not just to the rising million-dollar economy of Bharat but also have disrupted the chain of local employment of the region.

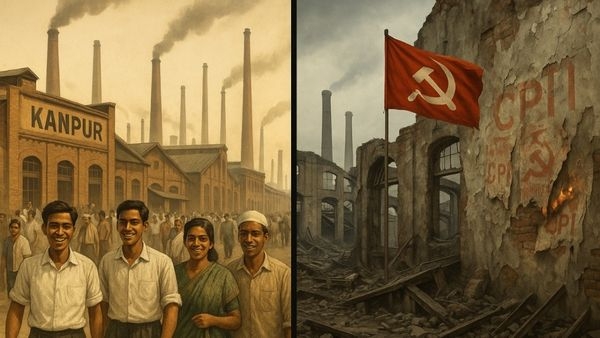

Kanpur: Once the Manchester of the East

Kanpur was once the industrial heartbeat of northern India, sharing the privilege of being synonymous with the textile and leather industries. From Elgin Mills, manufacturing the best cotton in the country, to the red-bricked Lal Imli textile mill factory of the British era, which served massive public and private sector enterprises, employing lakhs of workers and being the livelihood of lakhs of families.

However, beginning in the 1970s and accelerating through the 1980s, a series of aggressive strikes, lockouts, and trade union confrontations began to destabilise the industrial climate. Many of these actions were led or supported by communist-backed trade unions such as CITU (Centre of Indian Trade Unions) and AITUC (All India Trade Union Congress). Notably, Kanpur then saw the abiding representation of CPI leaders in Loksabha from the stretch of 1957 to 1971, after which the Janata Party’s Manohar Lal galloped its way via the Kanpur constituency, later passing a decade from 1980 to 1989 to Congress, then again, Kanpur falling into the hands of the red rule.

As a result, factory owners faced losses, productivity declined, and several units shut down. Even well-established public sector units like the British India Corporation collapsed under the burden of poor management and relentless labour unrest. Today, Kanpur is a pale shadow of its former self, struggling with unemployment, urban decay, and the flight of capital. Withholding the honour of Manchester of the East, the jewel of its crown now lies shattered, with its contribution to the Indian economy being reduced drastically.

Case of Modinagar

Modinagar was built as a model industrial township. With a cluster of textile mills, sugar factories, tanneries, and more, under the visionary leadership of Gujral Modi. Modinagar once offered employment to tens of thousands.

However, by the 1990s, the atmosphere turned hostile. Encouraged by left-leaning union leadership, workers began organising repeated agitations and strikes, ignoring the economic viability of their demands. Moreover, the Hind Mazdoor Sabha (affiliated with the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions) particularly protested violently, leading to the shutdown of major factories. The labour unions refused to accept technological upgrades or productivity-linked wages, while the red political interference ensured that workers may not get aligned with the notion of development with the rising industries.

Conclusion

The trade unions have always attempted to make themselves appear as a ray of hope to the workers, promising welfare to them, but in reality what they spew is excessive militancy, which has now contributed to the industrial decline of what was once the land of infinite possibilities, both for employment and economic courses. The militant, ideological, and inflexible trade unionism inspired by communist principles has proved to be economically disastrous in several Indian industrial hubs. And the case of Kanpur and Modinagar stands no different to it.

Article by

Kewali Kabir Jain

Journalism Student